The Bank of International Settlements (BIS), the banker to the world’s Central Banks, this weekend released its 83rd annual report. The conclusions are candid, reasonable and precisely what liquidity-addicted markets and traders were not expecting to hear [ever]. After 6 years of unprecedented monetary measures the BIS says costs are now outweighing any benefits and it is time for central banks to back down:

“Monetary stimulus alone cannot provide the answer because the roots of the problem are not monetary. Hence, central banks must manage a return to their stabilization role, allowing others to do the hard but essential work of adjustment.”

For those interested in a shorter summary of the full 204 page report, we have BIS General Manager, Jamie Caruana’s speech from the Bank’s Annual General Meeting yesterday in Basel. See: Making the most of borrowed time.

The BIS reminds of the time-tested truth that the way to wiser financial policies and behavior, is not through bail-outs and rescues but rather: admit, repent (which includes the need for actors to suffer the pain of their choices), reform and then recover. Here are some key highlights:

“…easy financial conditions can do only so much to revitalise long-term growth when balance sheets are impaired and resources are misallocated on a large scale. In many advanced economies, household debt remains very high, as does non-financial corporate debt. With households and firms focused on reducing their debt, a low price for new credit is not terribly relevant for spending. Indeed, many large corporations are using cheap bond funding to lengthen the duration of their liabilities instead of investing in new production capacity. It does not matter how attractive the authorities make it to lend and borrow – households and firms focused on balance sheet repair will not add to their debt, nor should they.

And, most of all, more stimulus cannot revive productivity growth or remove the impediments that block a worker from shifting into a promising sector. Debt-financed growth masked the downward trend in labour productivity and the large-scale distortion of resource allocation in many economies. Adding more debt will not strengthen the financial sector nor will it reallocate resources needed to return economies to the real growth that authorities and the public both want and expect.

Central banks have borrowed the time that the private and public sectors need for adjustment, but they cannot substitute for it. Moreover, such borrowing has costs. As the stimulus is sustained, it magnifies the challenges of normalising monetary policy; it increases financial stability risks; and it worsens the misallocation of capital.

Finally, prolonging the period of very low interest rates further exposes open economies to spillovers that are now widely recognised. The challenges are particularly severe for the emerging market economies and smaller advanced economies where credit and property prices have been rapidly growing. The risks from such a domestic credit boom at a late stage of the economic cycle are hard enough to manage. Strong capital inflows exacerbate such risks and challenges for market participants and authorities; and they expose economies to large sudden reversals if markets expect an exit from unconventional policies, as volatility during the past few weeks seems to indicate. In short, the balance of costs and benefits entailed by continued monetary easing has been deteriorating. Borrowed time should be used to restore the foundations of solid long-term growth. This includes ending the dependence on debt; improving economic flexibility to strengthen productivity growth; completing regulatory reform; and recognizing the limits of what central banks can and should do.

Extending monetary stimulus is taking the pressure off those who need to act. Ultra-low interest rates encourage the build-up of even more debt. In fact, despite some household deleveraging in some countries, total debt, private and public, has generally increased as a share of GDP since 2007. For the advanced and emerging market economies shown in Graph 2, it has risen by about 20 percentage points of GDP, or by $33 trillion – and rising government debt has been the main driver. This is clearly not sustainable.”

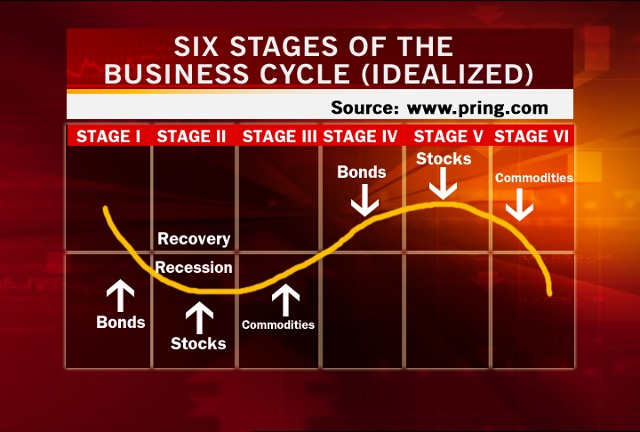

Don’t look now but the BIS head just admitted something that the Bernanke and legions of risk-sellers never do, that the global economy is now in the “late stage of the economic cycle” which as shown below means cash is king as the momentum of levered selling spreads and all asset classes drop together. What about the next economic recovery? First we have to go through the recessionary part of the cycle where risk assets are repriced toward and then below economic reality and reckless players lose their shirts once more.