The most recent credit bubble was born in 2002 when the Greenspan Fed cut rates to 1% and left them there for a year and ‘investment’ banks went loco fabricating and selling trillions in credit derivatives. Fourteen years later, we are still working through the mean reversion phase of the greatest credit bubble ever in human history. For those who don’t remember anything else, or who have come to believe that crazy is normal, it is easy to lose sight of what math and economic equilibrium will be sustainable once extreme credit creation and borrowing habits have receded once more. (And they will, because they always do–trees on earth don’t grow to the sky).

With the lion share of household savings held in realty (true for most of the developed world), and most people under-saved and banking on said realty as a store to help fund future retirement consumption, a key question must be: how much will people be able to pay for housing once they aren’t able or willing to borrow insane amounts of money?

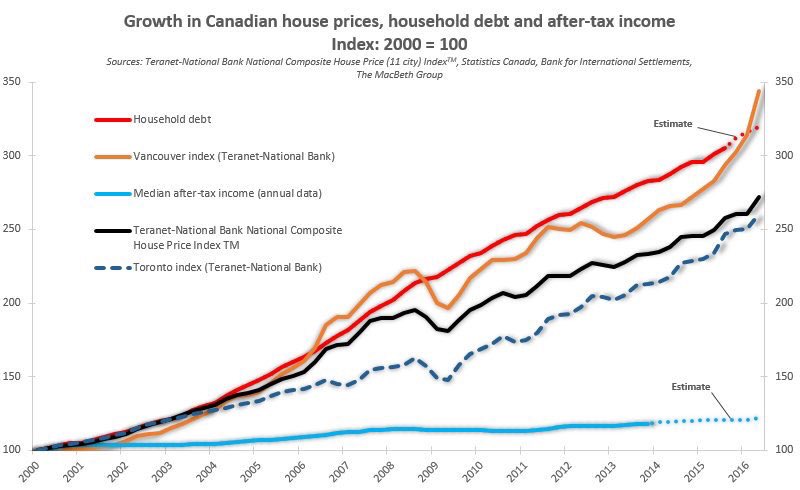

The answer: only as much as their annual after-tax income can pay for along with all their other living expenses. This chart below since 2000, offers perspective. Note the massive overshoot of Canadian household debt (red), and home prices (national average in black) above the flat-lined median household income (blue line) at the bottom of this chart.

We must appreciate that incredible price gains, much greater than long term norms, have been purchased, not by rising incomes, but by expanding credit derivatives, along with unsustainably low rates and lending standards. These are the factors that have enabled debt levels/asset prices far beyond reason today.

We must appreciate that incredible price gains, much greater than long term norms, have been purchased, not by rising incomes, but by expanding credit derivatives, along with unsustainably low rates and lending standards. These are the factors that have enabled debt levels/asset prices far beyond reason today.

In the longer run, debt servicing is necessarily tethered to available cash flow. Full stop. Unless the blue line of disposable income is about to move dramatically higher, then asset values will have to, at best, flatten out for a long time until debts can be paid down. Or prices will have to come down significantly from present levels to restore affordability. Banking on other outcomes is unreasonable.