A recent Charles Schwab study asked different age groups to estimate the net worth needed to feel ‘wealthy’ where they live. Not surprisingly, the amount estimated was higher for those aged 50+ than those in their 20’s–older folks tend to have more carrying costs and obligations. See: How much money do you need to be wealthy in America? But all age groups tend to dramatically underestimate the capital value needed.

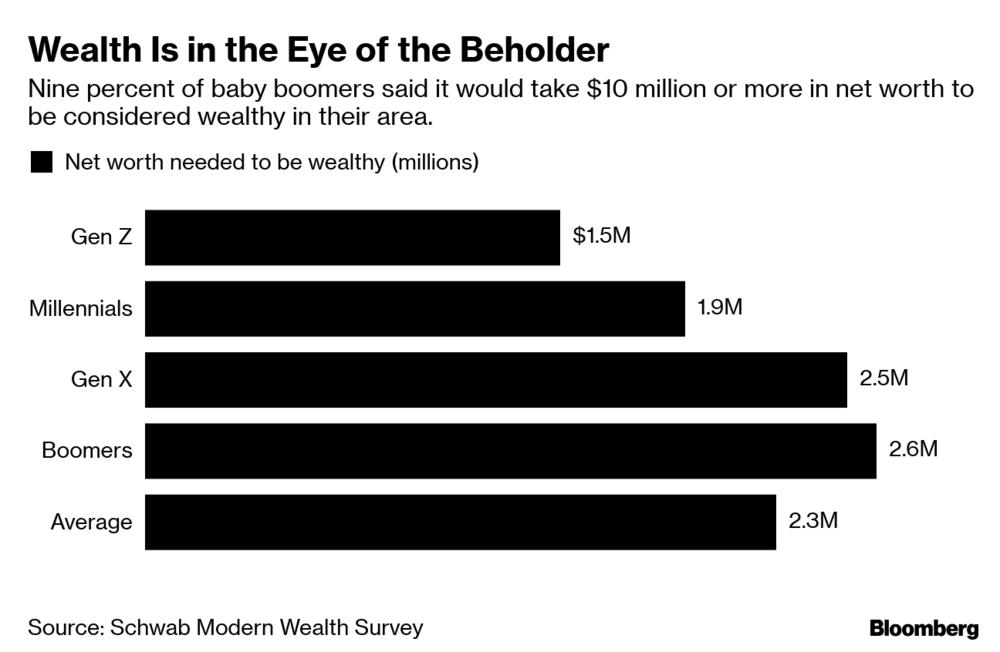

As charted below, those age 14 to 24 (Gen Z) estimated net worth (including one’s home) of 1.5 million U$ made one wealthy, while those aged 24 to 38 (Millenials) guessed $1.9 m was needed. Gen X (those 39 to 53) and Boomers (54 to 73) estimated $2.5-2.6m was the magic number.

39 to 53) and Boomers (54 to 73) estimated $2.5-2.6m was the magic number.

Meanwhile, the average household income in the US today is about $60k a year, and $C 70k a year in Canada. If the average household were to stop working and replace that same level of income from interest earned on capital-secure deposits today (paying 2.5% and less), one would need–outside of any home equity–at least $C 2.8m in Canada, and $U 2.4 m in America. And yet, few households earning 60 to 70k a year in pre-tax income today would think of themselves as wealthy.

Other studies report that half of the people over age 55 in North America have zero savings for retirement, and the half that does has a median amount of $104,000. One hundred and four thousand will produce a retirement income of about $2,600 a year.

Ten percent of those over age 50 have a defined benefit pension plan from their work. This fortunate group also tends to dramatically underestimate the capital value of it. When I ask people if they or their spouse have a pension, it is common for them to dismiss it as ‘just 30k a year’ or whatever the number. When I point out that a guaranteed income of 30k a year is like having 1.2 m in savings today, most are surprised. At the same time, the maximum US old age security income of 34k a year, and maximum CPP and OAS in Canada of 21k a year, also have large capitalized values of about 1.3m and 840k respectively.

Under-estimating the capital needed to reliably produce retirement income has resulted in widespread saving shortfalls over the past two decades. Trying to fix deficits with higher and higher-risk capital bets has the overwhelming probability of making shortfalls larger over time–and this is precisely what’s happened.

Financial/life plans that assume attainable yields along with pragmatic saving and withdrawal targets have a much higher probability of meeting our goals and needs. The sooner we accept and adopt honest math the better.