In explaining why highly levered, speculative cycles are so damaging to balance sheets and financial stability, I often reference the reality that when asset bubbles burst, prices drop and debt level rise, evaporating net worth rapidly and intensifying selling pressure.

The graphic below captures the point within the context of housing. Of course, the same applies to leveraged participants in security markets when prices tumble and margin and other debt borrowed to buy them does not. Margin calls and demand loan payments then force the borrower to add more cash or sell falling assets to raise it, accelerating the downward pressure on prices.

participants in security markets when prices tumble and margin and other debt borrowed to buy them does not. Margin calls and demand loan payments then force the borrower to add more cash or sell falling assets to raise it, accelerating the downward pressure on prices.

ABC Australia reports on the defaults mounting as home prices in many parts of the country are continuing to fall in 2019, even while unemployment rates remain historically low. See Mortgage delinquencies mount as more borrowers find their home is worth less than their mortgage.

Chinese stimulus spending and commodity stockpiling, along with incoming Asian money looking for land banks, helped drive a debt-fueled rebound in the economy and property markets into 2011-12 (Canada too). However, renewed commodity weakness in 2016, prompted the Australian central bank (RBA) to cut its bank lending rate to 1.5% from 1.75% where it has languished since. Today, the RBA cut its rate to a new historic low at 1.25% to try and increase record indebtedness further and put a bid under falling property prices. Australian households are already the world debt champions with 200% debt to disposable income.

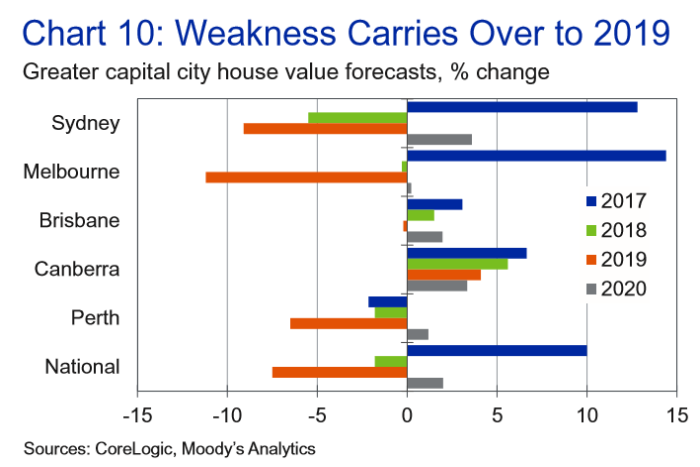

As shown in the chart below, even with low mortgage rates, home prices have continued to slide in several major areas since 2017. Sydney and Perth markets are down about 20% from their peak, and further weakness is expected through 2019, as mortgage delinquencies rise.

Sydney and Perth markets are down about 20% from their peak, and further weakness is expected through 2019, as mortgage delinquencies rise.

Price declines are already greater than those experienced in Australia during the 2008 financial crisis. This is causing optimists to predict that a price rebound is due next year. Historically, that would be a very short, shallow correction given the extremity of the overshoot in the last decade.

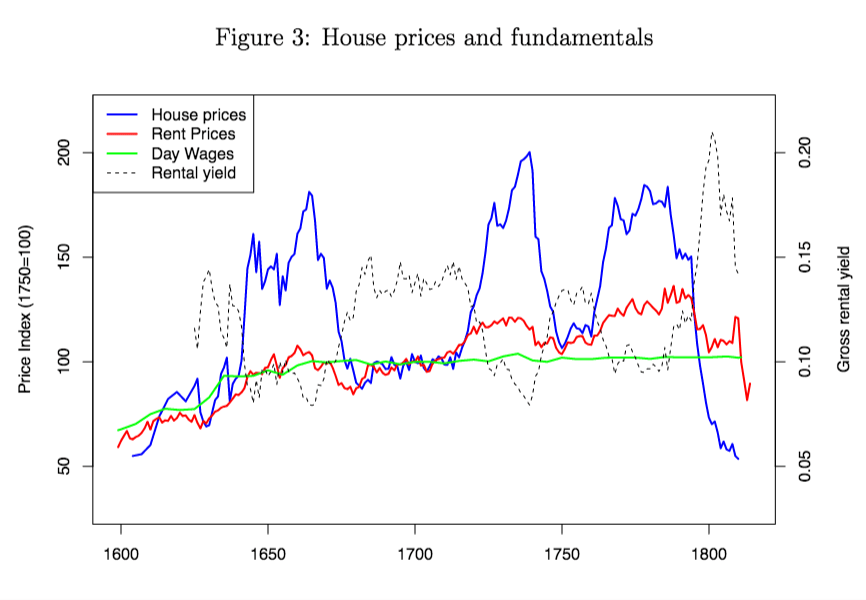

As explained in New Study of old real estate bubbles (1582-1810) finds two surprising similarities with modern bubbles, the correction phase after a housing bubble, commonly lasts many years. Researchers offer the chart below showing 200 years of Amsterdam home prices, incomes and ren t. Note that price spikes (in blue) which wildly disconnected from wages (in green)–came back down for years to restore affordability. At the same time, income yields (dotted line) leapt for investors who bought low from the owners and lenders liquidating at fire-sale prices.

t. Note that price spikes (in blue) which wildly disconnected from wages (in green)–came back down for years to restore affordability. At the same time, income yields (dotted line) leapt for investors who bought low from the owners and lenders liquidating at fire-sale prices.

There are always slightly different factors driving property boom and bust cycles, but price behavior has remained remarkably consistent in the aftermath. It is doubtful that this time will be different.