A repurchase agreement (repo) is a crucial form of short-term borrowing for dealers in government securities where they sell or swap government tbills on an overnight basis in exchange for cash and buy or swap them back the following day.

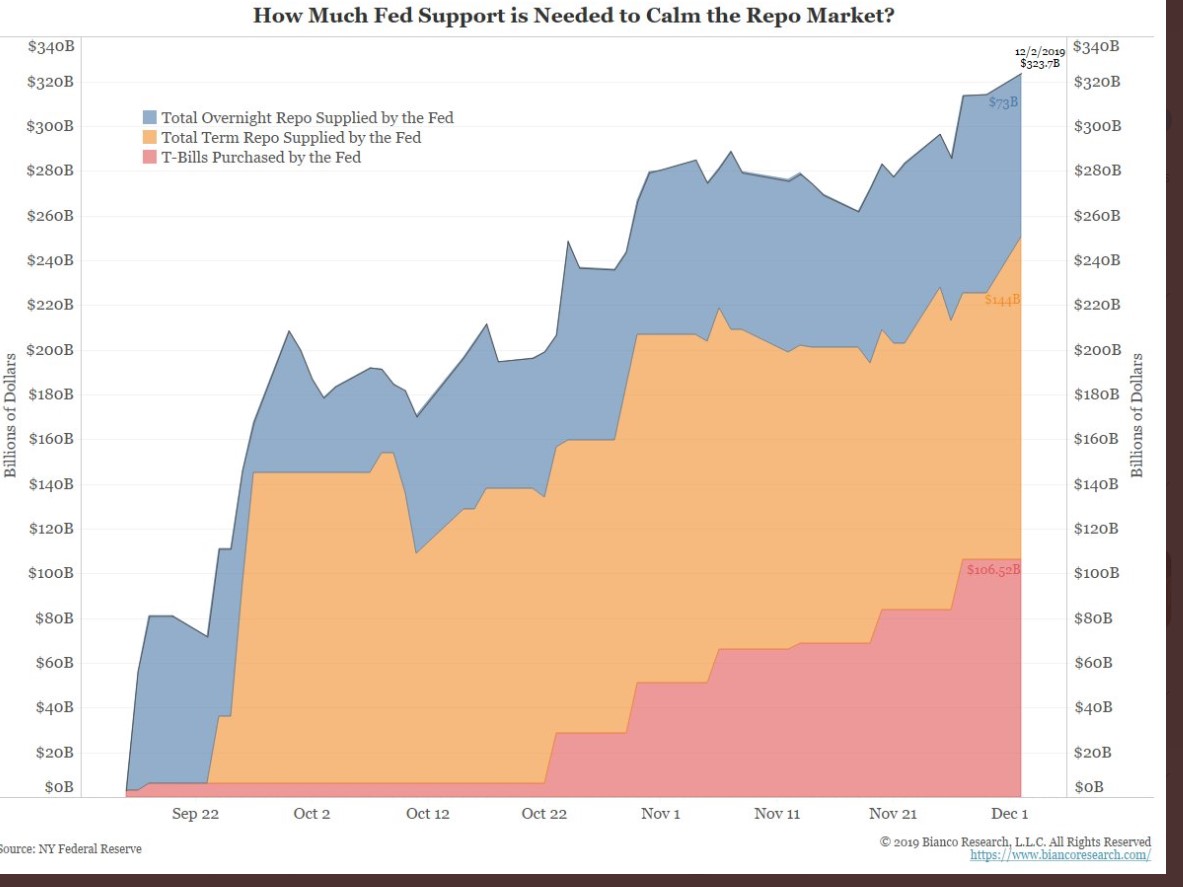

The New York Federal Reserve has funnelled hundreds of billions of dollars into repo markets since mid-September when a shortage of liquidity caused overnight borrowing rates to spike from about 2% to a stress-inducing 10% on September 17 to 18. A similar liquidity crunch sideswiped financial markets last December when overnight rates spiked to 6%. This time, funding strains have been more persistent.

The short-term repo rate is what bond dealers, hedge funds, and other market participants are charged for borrowing funds on a short-term basis, in return for highly liquid collateral such as Treasurys. The Fed was initially said to be supplying liquidity for third-quarter-end corporate tax payments in September and treasury auctions.

Trouble is, they have had to continue intervening on a near-daily basis over the last 2 months, and this is raising concerns about why banks would rather hoard cash at the Fed to pick up 1.55% than lend to each other for more.

At the current pace of injections, the Fed would own 20% of the T-bill market within six months compared with 1% today. This is on top of $60 billion in QE assets they are buying monthly, which has ballooned the Fed’s balance sheet back toward $4 trillion and enabled rampant financial speculation in corporate security markets with compounding risks and negative effect. See The repo market is ‘broken’ and Fed injections are not a lasting solution, market pros warn.

“This is now far bigger than anyone thought this was going to be,” Bianco said. “I think they’re hoping the market will magically fix itself. I don’t see why it would.”

Jim Bianco’s chart below shows the $320 billion in repo market support from the Fed up to December 2.