Two worthwhile reads this sunny August amid casino-quality financial markets:

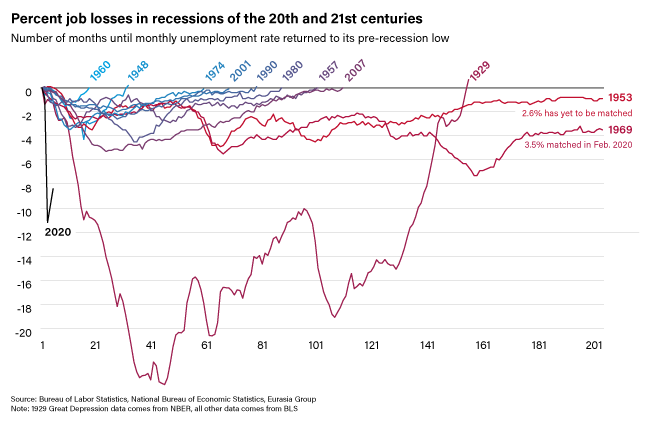

The first is foreign affairs expert Ian Bremmer’s latest piece in Time Magazine, see: The Next Global Depression is Coming and Optimism Won’t Slow it Down. It includes this illuminating chart of recessionary job loss and multi-year recovery times since the 20th century.

Bremmer discusses the jobs recovered so far in 2020 and adds:

Now for the bad news. First, that data reflects conditions from mid-June–before the most recent spike in COVID-19 cases across the American South and West that has caused at least a temporary stall in the recovery. Signs of corporate economic distress are mounting. And second and third waves of coronavirus infections could throw many more people out of work. In short, there will be no sustainable recovery until the virus is fully contained. That probably means a vaccine. Even when there is a vaccine, it won’t flip a switch bringing the world back to normal. Some will have the vaccine before others do. Some who are offered it won’t take it. Recovery will come by fits and starts.

He explains how depressions unfold and impact behaviour:

A depression is not a period of uninterrupted economic contraction. There can be periods of temporary progress within it that create the appearance of recovery. The Great Depression of the 1930s began with the stock-market crash of October 1929 and continued into the early 1940s, when World War II created the basis for new growth. That period included two separate economic drops: first from 1929 to 1933, and then again from May 1937 into 1938. As in the 1930s, we’re likely to see moments of expansion in this period of depression.

Depressions don’t just generate ugly stats and send buyers and sellers into hibernation. They change the way we live.

Another worthwhile article is by economists Carmen and Vincent Reinhart in the September 2020 Foreign Affairs publication, see The Pandemic Depression. The Global economy will never be the same. They offer important context for where we are now, and why partial re-openings and some bouncing asset prices do not signal economic recovery nor that the financial crisis has passed. Here’s a taste:

The pandemic has created a massive economic contraction that will be followed by a financial crisis in many parts of the globe, as nonperforming corporate loans accumulate alongside bankruptcies. Sovereign defaults in the developing world are also poised to spike. This crisis will follow a path similar to the one the last crisis took, except worse, commensurate with the scale and scope of the collapse in global economic activity. And the crisis will hit lower-income households and countries harder than their wealthier counterparts. Indeed, the World Bank estimates that as many as 60 million people globally will be pushed into extreme poverty as a result of the pandemic. The global economy can be expected to run differently as a result, as balance sheets in many countries slip deeper into the red and the once inexorable march of globalization grinds to a halt.

…Some important economies are now reopening, a fact reflected in the improving business conditions across Asia and Europe and in a turnaround in the U.S. labor market. That said, this rebound should not be confused with a recovery. In all of the worst financial crises since the mid-nineteenth century, it took an average of eight years for per capita GDP to return to the pre-crisis level. (The median was seven years.) With historic levels of fiscal and monetary stimulus, one might expect that the United States will fare better. But most countries do not have the capacity to offset the economic damage of COVID-19. The ongoing rebound is the beginning of a long journey out of a deep hole.