A new study from the Business Development Bank of Canada finds that 76% of the small and medium-sized Canadian businesses surveyed saw a decline in revenue and profits in 2020. Nearly half laid off staff, while about 39% of entrepreneurs have taken on more debt to survive. See Indebted Canadian businesses more “fragile” than during the first wave: BDC.

The good news is that recent experience has shocked many households and businesses to focus on greater efficiency, reduce costs, and build up cash savings–critical behaviours needed to restore financial strength.

The bad news is that as the recession and under-employment continue (see: Deloitte’s estimates that 70% of jobs lost in Pandemic may not return before 2022), many lack the income needed to rebuild. Many are more indebted now than they were six months ago.

Two-thirds of small business owners say they’re in a worse situation now than before the pandemic. And insolvency trustees are warning of similar trends in Canadian households. See: What to do if you can’t pay deferred mortgage payments.

New Bank of Canada chief Tiff Macklem acknowledged Canada’s debt-linked fragility today in a speech: “The bottom line is that the private and public sectors together need to be acutely aware of financial system risks and vulnerabilities as the economy recovers.”

Falling commercial and residential rents are much needed for reducing overhead costs, but property prices must also follow, and the income and balance sheet losses will hurt present owners and lenders. See, Manhatten apartments haven’t been this cheap to rent since 2013, and In an echo of Toronto, condos flooding the market in Montreal.

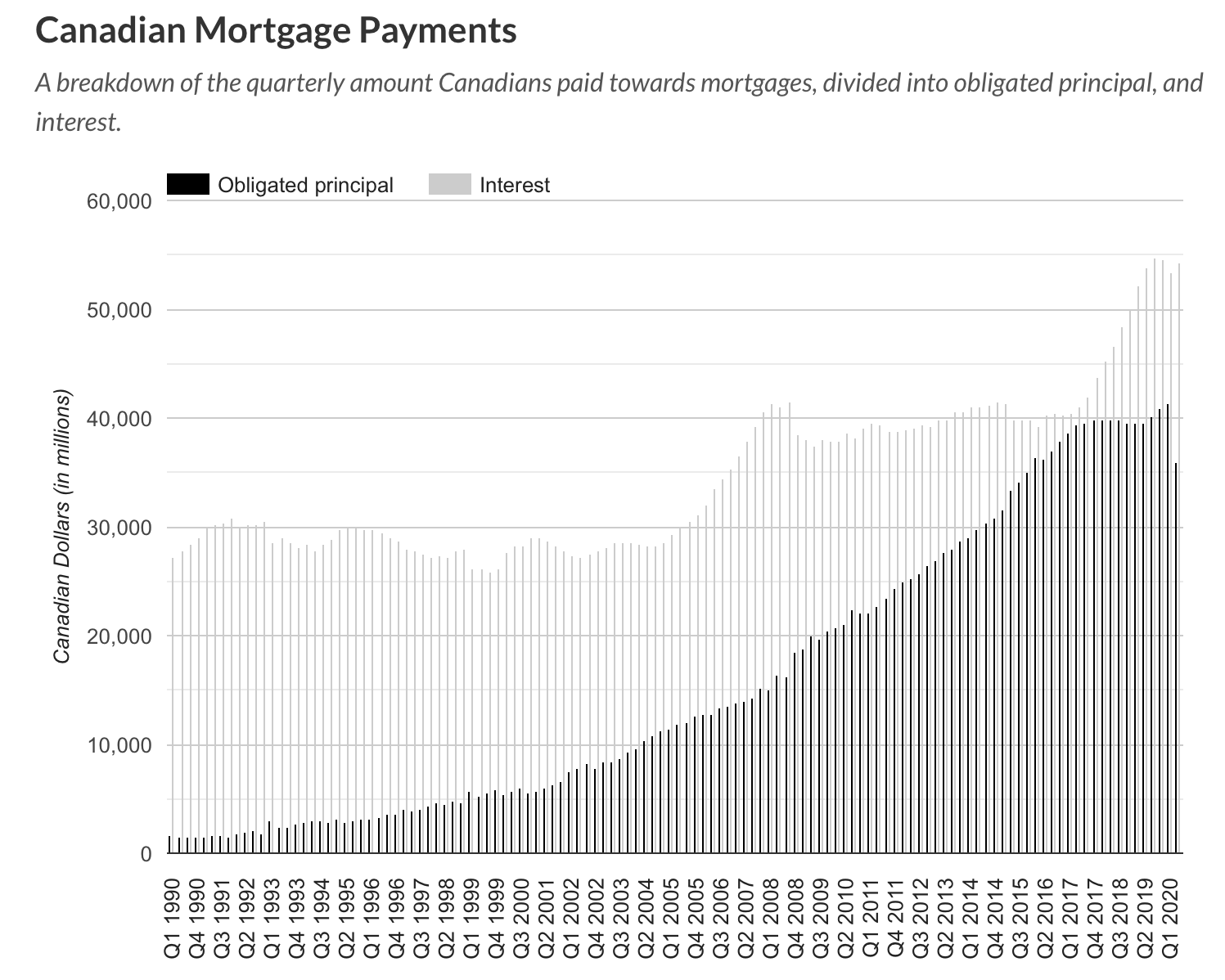

As shown in the chart below (source: not indicated), since 1990, central banks don’t admit it, but the polic y obsession with lower and lower interest rates is the cornerstone of our present fragility. As the interest component of mortgage payments flatlined from 2008 to 2017, prices paid soared along with the debt’s principal portion. This inflated debt is now a heavyweight on consumption and saving ability for years into the future.

y obsession with lower and lower interest rates is the cornerstone of our present fragility. As the interest component of mortgage payments flatlined from 2008 to 2017, prices paid soared along with the debt’s principal portion. This inflated debt is now a heavyweight on consumption and saving ability for years into the future.

Simultaneously, the low rates that have enabled record debt, unaffordable shelter and other asset bubbles have worsened retirement prospects worldwide as prices are too high today to produce yields anywhere near what most financial plans are banking on. From 6% in 2000, secure deposits are now yielding less than 1% and dramatically undershoot the presumption of 4% as a sustainable withdrawal rate from retirement savings. As noted in the 2020 Natixis Global Retirement Index released this week:

One of the biggest threats to retiree wellbeing is low-to-negative interest rates, which can make earning a decent income from safe investments nearly impossible. The report found that for 16 of the 44 countries studied, the five-year average for real (inflation-adjusted) interest rates had gone negative. In the 2016 version of the report, just one country, the U.K., fit that bill.

To gain financial viability, social stability, and yield–critical cash flows for compound growth and income withdrawals–asset prices must first give back years of bubble gains. In the process, a growing number of people will seek to liquidate assets to reduce overhead and raise cash. A buyer’s market is coming for most things, but only those who have patiently prepared in advance will be ready to buy.