As I have noted many times, most people today have unrealistic expectations regarding what income their savings can ‘safely’ produce in retirement and, therefore, the amount of savings they need to sustain their spending once retired.

A sustainable rate of withdrawal is one that can continue throughout our lifetime without consuming all of our principal before we die. For those with goals of leaving funds for beneficiaries, a safe withdrawal rate is the one that can be taken while still preserving desired funds for our estate.

Twenty years ago, GICs and capital-secure bonds yielded 5 to 6% annually, and 5% was a commonly presumed sustainable withdrawal rate (after fees and before tax). Today, however, most capital-secure deposits are yielding less than 1%.

A million of savings once produced $50k in annual income safely; today, that same million produces maybe $10k a year.

This has caused many people to move their savings into less secure holdings like equities, corporate debt, real estate, commodities, and other derivatives, hoping to reach their capital goals and desired retirement income withdrawals. In the process, these risky assets have become extremely over-priced on historically reliable metrics and offer the hideous opportunity set of both high capital risk and lower-income yields (yields move inversely with purchase price).

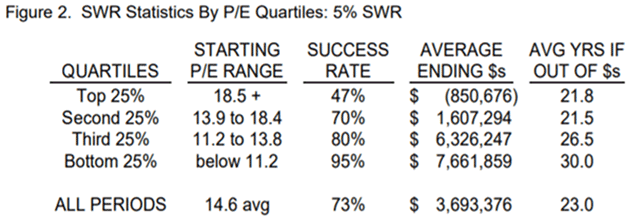

High asset valuations greatly increase the recurrence of large capital drawdowns that undermine compound returns and our savings’ longevity. As pointed out by John Mauldin this week, and as shown in the table below courtesy of Crestmont Research Inc., the price we pay to buy an investment asset is the most defining feature of whether returns achieve or fail capital and income targets over time.

When we purchase equities in the bottom 25% of historical valuations and try to withdraw 5% annually to our death, we have a favourable 95% probability of not outliving our savings.

However, when assets are bought in the top 25% of historical valuations, and a 5% annual withdrawal rate is attempted, we have a grim 53% probability of consuming our savings within 21 years. Depending on one’s life expectancy, these are highly unsatisfactory odds.

Given that today’s asset valuations are in the top 10% of historical occurrences, capital longevity prospects for present owners are even shorter. This reality needs to be taken into account today in planning when to retire, what we wish to spend and how to allocate our savings. As John Mauldin explains:

If your financial planner says you can take out 5% per year “safely” based on a 60/40 (stocks to bonds) portfolio, then you should take your papers and walk out the door.

Furthermore, many planners use a total return model, which starts in the 1920s and shows that over time markets will give you an 8 to 9% return. They simply a (and lazily) plugin that 8–9% number for every future year, assuming that time will take away the effects of a bear market and recession. And that is probably true if you have 80 to 90 years. If, however, you are retiring when the markets are at a very high valuation, like now, your model will likely give you terrible advice.

Pension funds are going to get devastated in this decade. So are many retirees. And it all comes from bad models on top of more bad models.

There are, however, many practical steps that we can take to increase our financial security and capital longevity prospects. At my firm, we help our clients and ourselves to do exactly this every day–and it’s generally the opposite of what mainstream finance recommends.