Commodity prices and inflation expectations (below since 1995) have been following government and central bank stimulus flows higher over the past six months. This is no all-clear sign for risk markets or the economy—quite the opposite.

Treasury yields have moved higher for the ride. From a low of .43% on August 20, 2021, Canada’s 10-year yield is now 213% higher at 1.349%, and US Treasury yields 178% higher from .51% in August to 1.42% today.

Treasury yields have moved higher for the ride. From a low of .43% on August 20, 2021, Canada’s 10-year yield is now 213% higher at 1.349%, and US Treasury yields 178% higher from .51% in August to 1.42% today.

Near-term rates are more hinged to central bank policy rates, so they have moved less, but the 2-year Canada yield is still up 72% from .148% at the start of the year to .255% today and the US 2-year yield at .129%, up 17% from last August.

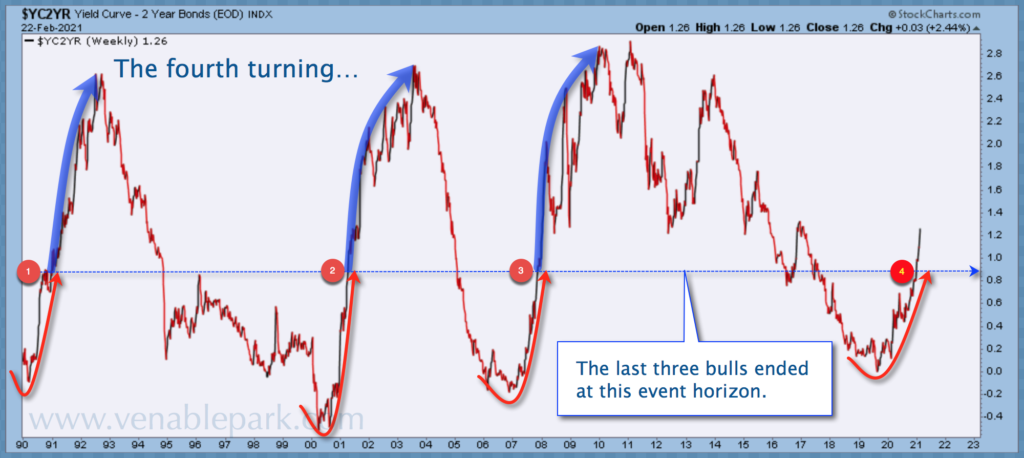

The difference in the 2 and 10-year rate moves have served to steepen the yield curve, as shown below in my partner Cory Venable’s chart of the US 10 minus 2-year spread since 1990. The spread between these two closely watched yields moved above 1.25 this month and significantly above the .81 threshold breached at the end of December.

In the past three economic cycles, a breach of the .80% spread line (dotted above) saw the gap max at 2.6% amid an intensification of economic recession. This then prompted another relapse in longer-term rates (see three blue arrows marked) as over-optimistic growth expectations downsized. We suspect a similar pattern will follow as 2021 progresses.

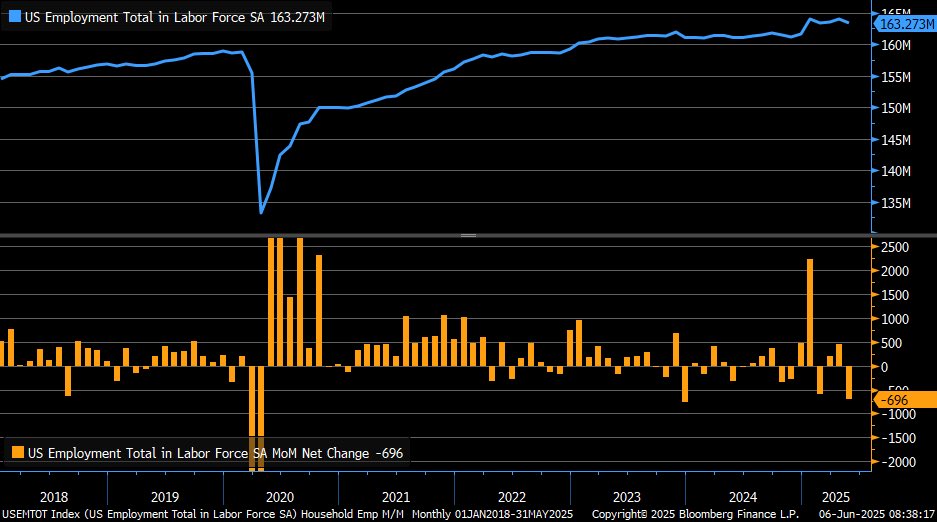

Higher commodity and interest rates weigh heavily on spending and recovery at this part of the economic cycle because jobs remain missing in action, and employment losses during this recession are heavier than average.

With thousands of small businesses now closed, Canada is missing some 850,000 jobs and America about 9.4 million. For some big picture, the US employment to population ratio today is 57.5%, down from 61.1% before the 2020 recession began, and compared with 59.4% at the worst point of the 2008-09 Great Recession (source: Rosenberg Research). It typically takes years before the employment ratio can reclaim its prior cycle high.

Low-interest rates can be constructive in helping people pay back borrowed funds faster. But when they encourage more borrowing for the already heavily indebted and more expensive home prices, lower rates have the opposite effect: extracting directly from future spending potential. This is us.

If historical norms hold, longer bond yields may rise further, and the 10-2 curve steepen perhaps another percent. This should then provide another valuable buying opportunity for government bonds and the US dollar as equity and commodity prices relapse into the next leg of the bear market that was temporarily interrupted last March.