I have explained many times that central banks worry that falling inflation (disinflation) and outright deflation reduce the incentive for spending and capital flow into financial markets.

The theory goes that if consumers and businesses believe that prices will be flat or lower in the future, they have less incentive to spend today. Moreover, if savers are not threatened by the fear of inflation eroding their purchasing power, they have less incentive to buy the risky securities that financial firms and public corporations continually seek to sell them.

Even though inflation has averaged less than the official 2% target since 2007, recently, U.S. Fed head Powell threatened that he is willing to tolerate inflation above 3% if that’s what it takes to keep prices moving up.

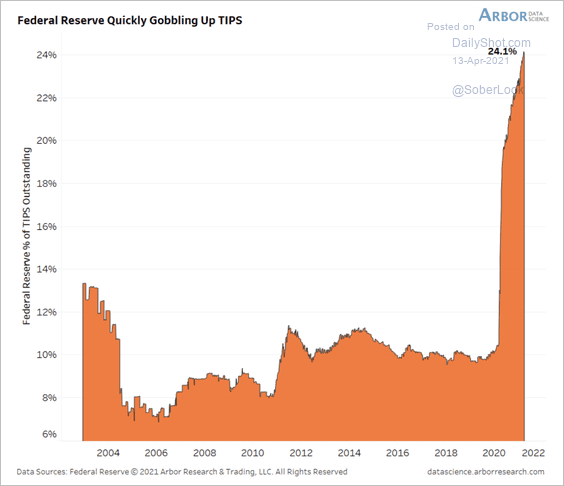

Apparently, that includes buying up inflation-linked treasuries (TIPS). As shown below, the US Fed has gobbled up just over 24% of the outstanding TIPS market in 2021. The principal of a TIPS increases with inflation and decreases with deflation, as measured by the Consumer Price Index. In buying these bonds, the central bank intentionally boosts their price and inflation expectations along for the ride.

Taking the bait, commodities and corporate securities have spiked higher with inflation expectations, as individuals and trend-following funds have ratcheted up risky holdings in the hopes of outrunning capital shortfalls.

Taking the bait, commodities and corporate securities have spiked higher with inflation expectations, as individuals and trend-following funds have ratcheted up risky holdings in the hopes of outrunning capital shortfalls.

This is a familiar pattern. Each time central banks have redoubled efforts to suppress interest rates and boost risk-appetite in financial markets, funds have flowed out of lower-risk bonds and cash and into commodities, stocks, junk debt, and other risky assets. For a while.

Then, in a self-fulfilling circle, the incoming capital spikes commodity prices and inflation expectations and lowers bond prices, which increases bond yields/interest rates, which leads to reduced borrowing capacity and spending, disappointing growth. Then funds reverse back out of commodities and corporate assets and into perceived safe havens like government bonds and the U.S. dollar once more.

We never know the precise moment of inflection in real-time but realizing that central banks are Oz-like and knowing what inputs to measure and map is a huge help in anticipating where capital is due to flow next.