Fed Chair Powell says acceleration in monetary tightening may be warranted.

Perhaps it was part of his renomination agreement that he at least acknowledges the strain on households a nd small businesses as they seek to service high indebtedness while paying more for goods and services from less income and receding government support.

nd small businesses as they seek to service high indebtedness while paying more for goods and services from less income and receding government support.

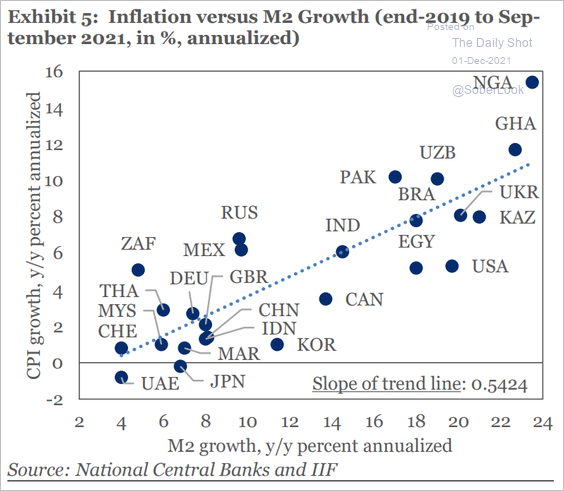

There’s a direct connection here, of course. As shown on the left, courtesy of the Daily Shot, the countries that have inflated their M2 money supply the most since 2019 (x-axis below) have seen some of the highest consumer price inflation (y-axis).

For a few months in 2020, it looked like some of that gushing money supply was making its way into the economy as small and medium-sized companies tapped bank credit lines for emergency liquidity. Then in Q2 of 2021, the global credit impulse (which measures the pace at which the flow of credit is growing to households and businesses) turned sharply negative as one-off support to the private sector stalled. For their part, public companies bypassed bank lending standards by selling tons of debt at ultra-low yields to indiscriminate “TINA” buyers.

Since then, cash injections from central banks mostly just funnelled into asset markets, driving up the price of critical commodities and housing and counter-productively reducing future growth by inflating present consumption and debt well beyond any gain in incomes.

As shown below in my partner Cory Venable’s chart of the commodity index (CRB) since 2001, the price bounce off the March 2020 bottom was sharp, to be sure; but only back to the 2009 lows, before oil and gas began tumbling after other CRB constituents once more.

For its part, the US dollar index (DXY) didn’t buy Powell’s accelerated tapper talk. Rising since May, the DXY did touch a 52-week high on November 24 but yawned in ongoing consolidation on Powell’s testimony. If currency markets believed the Fed was serious about accelerated tightening, the greenback would have picked up its pace of accent.

In reality, the stronger dollar is already working at cross-purposes to the Fed’s inflation aspiration. The rising dollar brings lower commodity prices (92% priced in USD) and higher debt service costs for a world that owes more U$ debt today than ever before.

Regardless of new COVID variants, the global economy was already slowing into 2022 on pent-down demand, lower private sector incomes, and governments retreating from earlier deficit spending programs.

Presently, the US Fed is expected to end its bond-buying in the first half of 2022 and then hike rates twice by year-end, while the Bank of Canada is expected to hike its policy rate five times. Sure thing. They will try hiking into a downturn until deflating asset markets give cause for pause once more. And then a return to more asset buying. We are following Japan’s policy playbook, after all. But lest anyone forget, decades of near-zero rates and asset-buying have not stopped Japan’s asset prices from deflating over the last 30+ years.

Monetary policy should have been normalized years ago. Central banks should not have cut rates below 2%; they should not have spent trillions buying financial assets–we should never have allowed them such unaccountable power. But now we are here, and our fragile financial markets and economy face the payback period.

Some risk always materializes to topple unsustainable systems; this is not about a virus. Prudent management plans for problems and builds up buffers in advance.

Individuals should understand where they are and what they can do to protect themselves.