It is important to understand that advertised investment returns typically assume that all interest and dividends are reinvested with no withdrawals for fees or spending–ever.

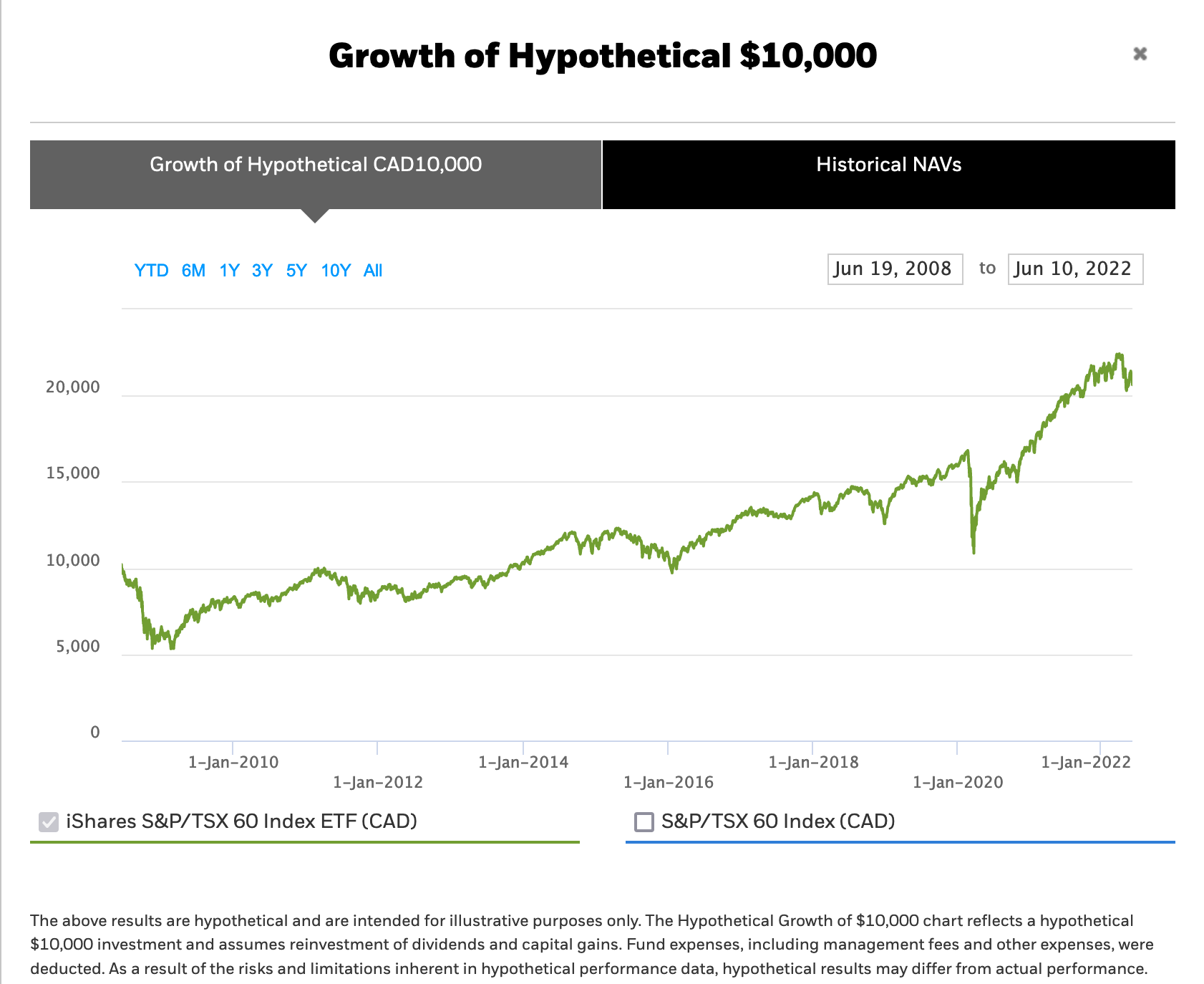

In this way, as charted below and here, the notional annual compound return of Canada’s investable TSX 60 index (XIU) over the 14 years to June 10, 2022, was advertised as 5.05%, with 3.16% of that assumed to have come from reinvestment of the 2.6% average annual dividend yield.

Hypothetical returns indeed; in reality, intermittent deposits and withdrawals are par for real life, and actualized returns rise and fall with asset valuation cycles.

Case in point, at its 22,000 peak in April 2022, Canada’s TSX composite index had managed to appreciate 3.4% per year since 2008. As shown in my partner Cory Venable’s chart of the TSX index below, as the market dropped into the end of May, capital returns over the prior 14 years had eroded to 2.64% annualized.

Under 20,000 today, just 10% below its April peak, the annualized capital appreciation rate for the TSX since 2008 has fallen to 1.89%.

Historically, the average S&P 500 decline has been 29% over 12 months if the economy was not in recession and 42% over 16 months when it was; the TSX has roughly tracked along for the ride.

A further 32% decline for Canadian stocks from here (taking the index back to the 13,000 range) is our base case and a relatively mild outcome given the present extremities of over-valuation, indebtedness, and economic deceleration. Such a price move would retest the March 2020 COVID crash low and evaporate all capital appreciation for the TSX for the past 14 years.

As horrible as that would feel for many, the truth is that negative returns have been the most probable outcome for conventionally allocated portfolios because irrational exuberance has repeatedly goosed valuations far above historical norms since the late 1990s.

A return to the long-term historic mean on critical financial metrics will require years where ratios stay below average–that’s how averages work.

The masses do not understand mathematical probabilities, or they don’t turn their minds to them. Like engineers, financial analysts are trained to take measurements, assess and recommend best construction practices for efficiency, stability and safety. That’s actually the easy part. However, most work for entities where they’re paid to ignore time-tested formulas and principles to encourage people into risky structures.

That a building or bridge goes years before collapsing doesn’t mean it was soundly constructed, nor that those who warned about its frailty were wrong. The same is true in finance.