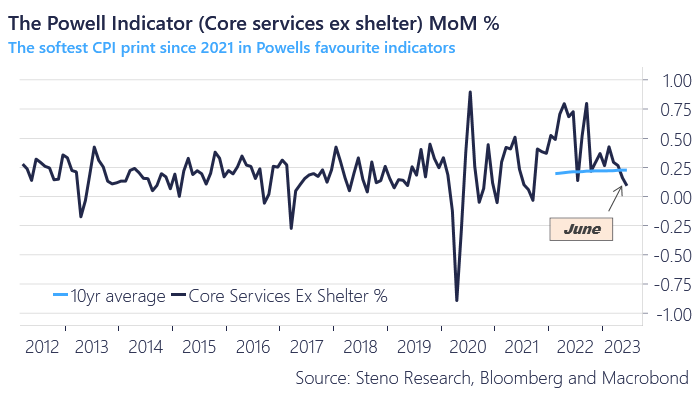

The June US Consumer Price Index (CPI) came in at a 3% annualized rate, down from the pandemic-inflamed peak of 9.1% a year ago. FOMC chair Powell has said that ‘super-core’ services ex-shelter (which excludes food, energy, rent and used car prices) is his preferred inflation gauge, and (as shown below) it came in at 1.4% annualized versus 4% in January, down sharply from 3.1% in May and below the 2.5% average over the two years pre-pandemic (2018 and 2019). Shelter costs make up more than a third of the CPI index, and year-over-shelter CPI moved lower for a third consecutive month to 7.8% in June from 8.2% in March (the highest since 1982). To reach the 2% CPI target, housing is the bogey that must be deflated, and that means holding the credit hand brake with the good, bad and ugly.

Shelter costs make up more than a third of the CPI index, and year-over-shelter CPI moved lower for a third consecutive month to 7.8% in June from 8.2% in March (the highest since 1982). To reach the 2% CPI target, housing is the bogey that must be deflated, and that means holding the credit hand brake with the good, bad and ugly.

Focused on that task, the Bank of Canada (BOC) announced another 25bps of monetary tightening, taking its overnight rate to 5% for the first time since April 2001 (!) In addition, the BOC is shrinking its balance sheet (QT) as large amounts of bonds mature and roll off monthly.

Floating rates are immediately affected. That’s good news for savers: the interest rates on investment savings accounts are moving above 5%–a ten-fold increase in 16 months.

For debtors, tough times are getting tougher. Prime borrowing rates offered by commercial banks in Canada are moving to 7.2%, variable rate mortgages around 6% and home equity lines of credit (HELOCs) around 7.7%. Those looking to qualify for new mortgages need to do so in the 8 percent range. That math is stark: a household earning $200k a year with zero other debts can qualify to borrow a maximum of $621k (play with the numbers here) and be saddled with a mortgage payment over $4,600 a month (plus taxes, utilities and maintenance). Many existing owners will need to sell as mortgage terms come up for renewal.

The next stress accelerant will be lost income. Policy tightening is intended to reduce employment (“wage pressures”), and it will. The BOC sees Canadian GDP slowing to a 1% annualized rate in the second half of 2023 and early 2024, with GDP growth of just 1.2% in 2024.

On the upside, shelter prices are already heading lower in many areas, and that’s likely to spread and improve affordability over the next several quarters. Housing downcycles historically have taken four to six years before prices bottom.

The US Fed is expected to hike another 25 bps at its July 26th meeting. But recessionary odds are mounting that this will be the final hike from central banks in Canada and America. Financial markets are celebrating that thought and the hope that rate cuts will soon come to the rescue.

But here’s the thing: the impact of tighter credit conditions will slow the economy over the next year to 24 months, even if no further hikes take place from here.

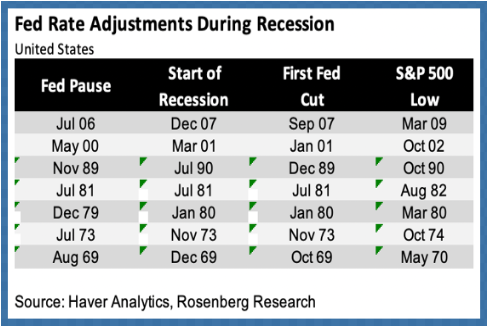

Not only that, in past cycles, the average Fed pause between the last hike and the first cut was eight months. As shown in the table below, in every case, the stock market did not bottom until 13 to 33 months after the last hike (see S&P low dates).