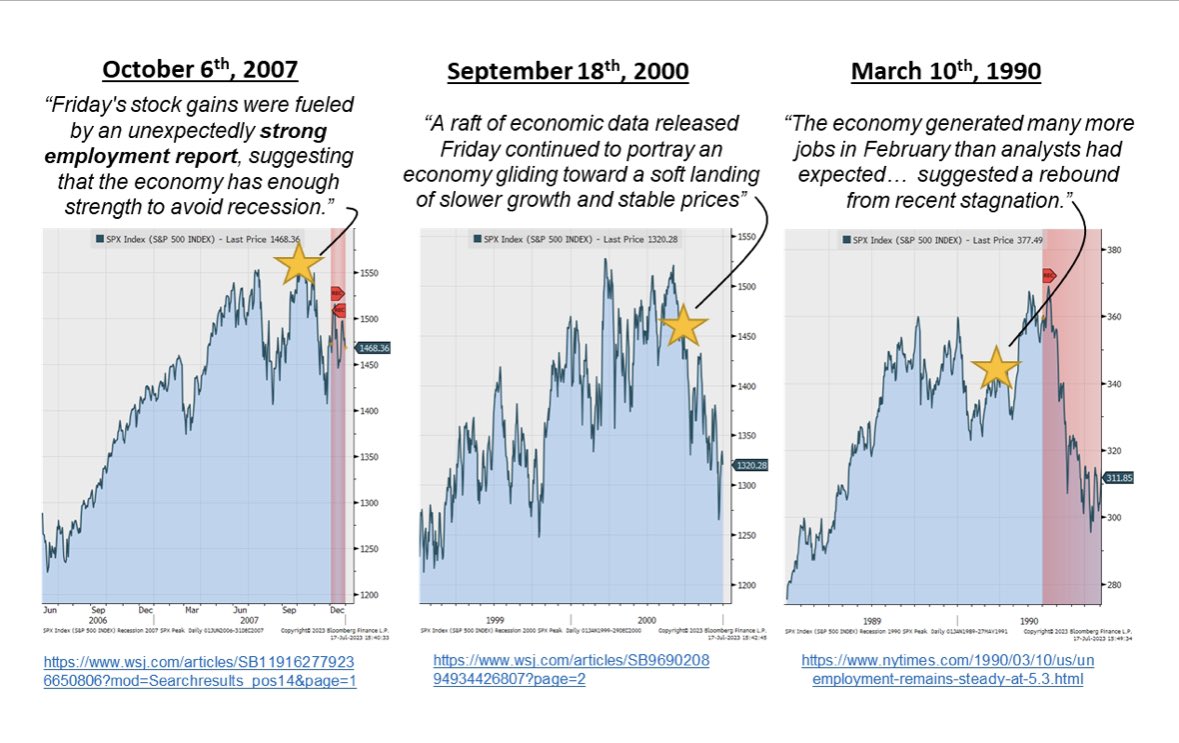

Bullish sentiment roared back in the first half of 2023 on the blind belief that low unemployment numbers mean that this time is different and the sharpest monetary tightening in 40 years is not triggering a recession.

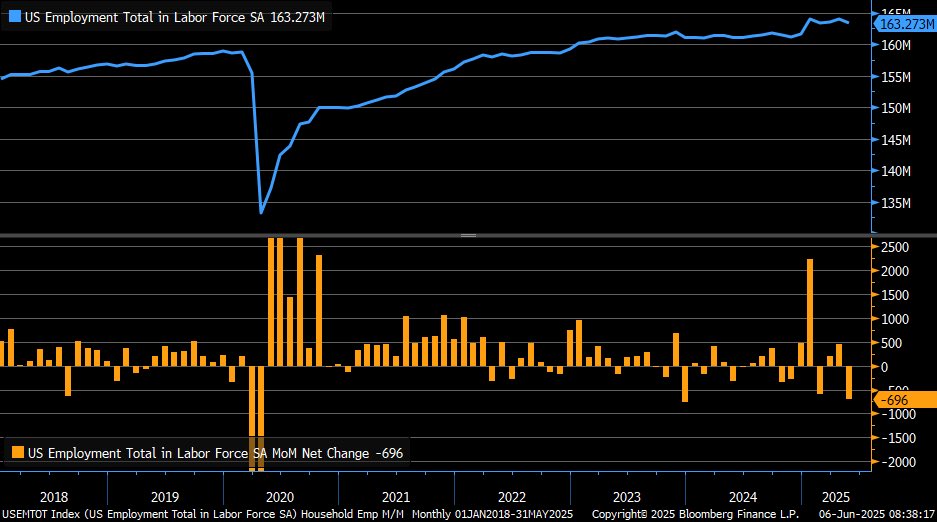

In reality, changes in unemployment lag behind changes in monetary policy by 12 to 24 months, and mainstream commentators make premature all-clear proclamations before the worst of market losses, every cycle. The chart below, courtesy of Michael Kantrowitz, evidences similar overconfidence during the 1990, 2000 and 2007 downcycles. Meanwhile, last week’s jobs data showed leading signs of employment distress with declines in the average work week (to the lowest since April 2020), temporary help, and full-time jobs, both in Canada and the US. The number of people taking on more than one job to make ends meet leapt in June and July to the highest since January 2020.

Meanwhile, last week’s jobs data showed leading signs of employment distress with declines in the average work week (to the lowest since April 2020), temporary help, and full-time jobs, both in Canada and the US. The number of people taking on more than one job to make ends meet leapt in June and July to the highest since January 2020.

Others point to strong consumer spending as evidence that households can sustain economic growth. In reality, consumer spending as a percentage of GDP (below in blue since 1947) always soars in the run-up to recessions and typically stays in an uptrend until after the end of the recession. Gross Private Domestic Investment (GPDI) as a percentage of GDP (below in green), on the other hand, typically falls heading into recessions (marked in grey). The divergence between these two indicators year to date is entirely consistent with the onset of past recessions. ECRI elaborates on their website here.