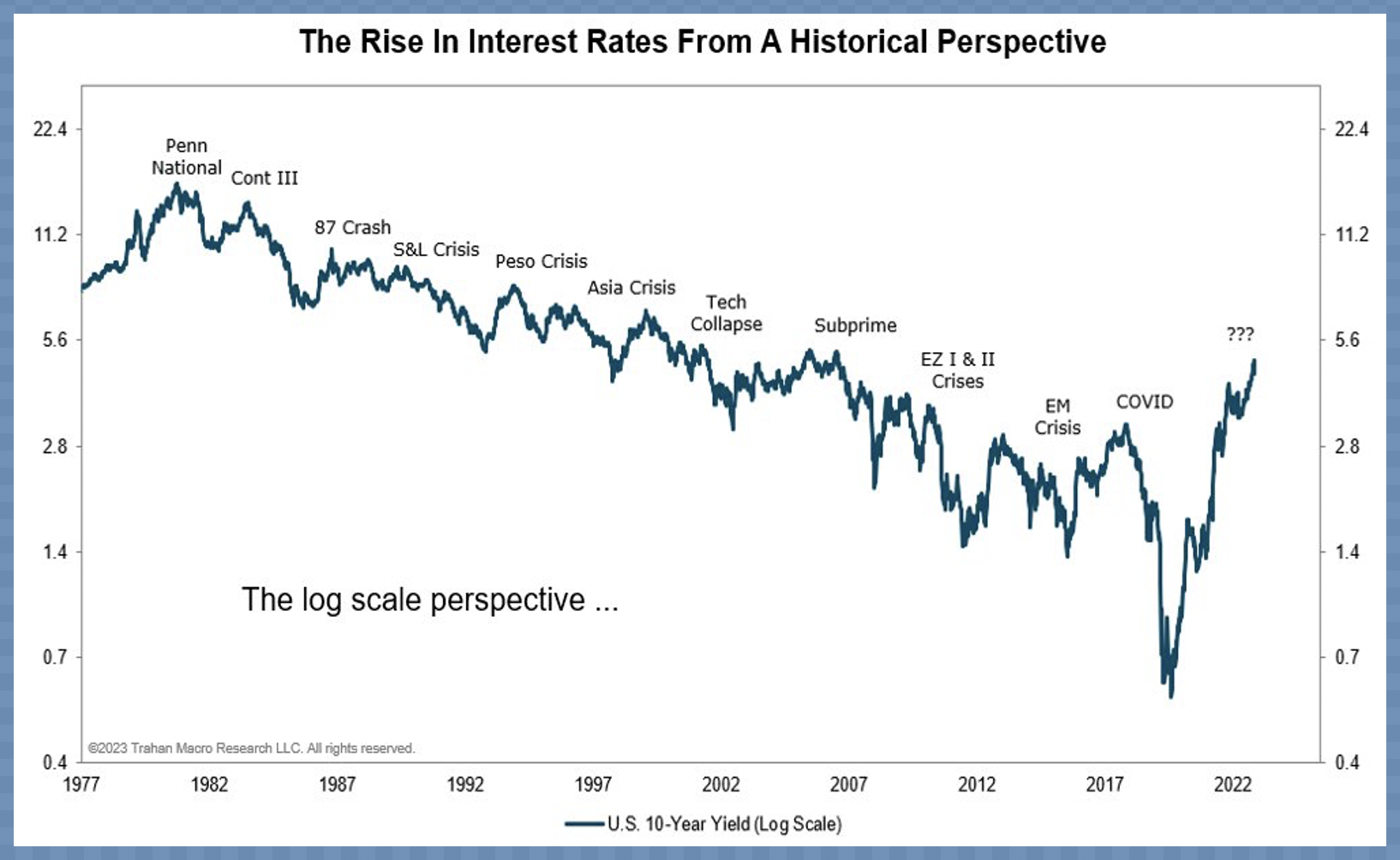

After 475 basis points (bps) of rate hikes between March 2022 and July 2023, Canada’s economy has ground to a halt, with economic activity contracting at a 1.1% annualized rate in the third quarter. Per capita, Canadian GDP has contracted for the past five quarters (below courtesy of RBC Economics).  The rate of change matters most, and as shown below, since 1977, courtesy of Trahan Macro Research, 2022-2023 was the most aggressive tightening cycle in more than 50 years.

The rate of change matters most, and as shown below, since 1977, courtesy of Trahan Macro Research, 2022-2023 was the most aggressive tightening cycle in more than 50 years.

With spending off the boil, the inflation rate (CPI) has fallen from 8.1% in June 2022 to 3.1% in October. Futures markets expect the Bank of Canada to stand pat with a fifth consecutive pause tomorrow and a first 25 bp cut by March or April.

With spending off the boil, the inflation rate (CPI) has fallen from 8.1% in June 2022 to 3.1% in October. Futures markets expect the Bank of Canada to stand pat with a fifth consecutive pause tomorrow and a first 25 bp cut by March or April.

Emerging economies had no choice but to follow suit to defend their currencies. But as global demand slumps, emerging economies in Latin America, Central and Eastern Europe have already returned to easing in 2023, with Chile, Hungary and Poland lowering their benchmark interest rates by a cumulative 150 bps to the end of November.

If North America is not in recession already, it is typical for one to start within six months of the last rate hike (i.e., January will be six months since the July hike) and within two years after the first (i.e., by March 2024). Historically, this suggests that the stock market may bottom around the fall of 2024, with corporate earnings and employment troughing several months later.

This typical pattern is on display in the world’s second-largest economy, where the Chinese central bank has already cut the one-year loan prime rate— the peg for most household and corporate loans–and pumped liquidity into the financial system. Not surprisingly, Beijing’s rescue efforts have proven no quick fix for an imploding real estate market, faltering economy, and rising unemployment where Chinese borrowers are defaulting in record numbers. Yesterday, China’s CSI 300 stock Index dropped to its lowest price level since February 2019.

In the 2001 and 2008 recessions, the US and Canadian central banks cut policy rates by 500 bps. There are hopes they may want to avoid a return to the zero bound this time and limit easing to 300 bps to hold overnight rates around 2 percent. That would be better for longer-term financial stability, but we shall see.

Either way, there are key takeaways here. While 80% of equity market losses have historically happened while central banks cut interest rates, Treasury prices have moved in the opposite direction. As shown below, courtesy of Bloomberg, a 300 bp rate-cutting cycle has historically generated an average 12-month return of about 18% on a 2- to 10-year government bond portfolio. Longer-dated Treasuries have traditionally delivered even higher returns but with much greater volatility.

A greater than 300 bp cutting cycle would suggest potentially larger capital gains for Treasuries but also a very bad economy, leaping unemployment and a deeper-than-average bear market for stocks.