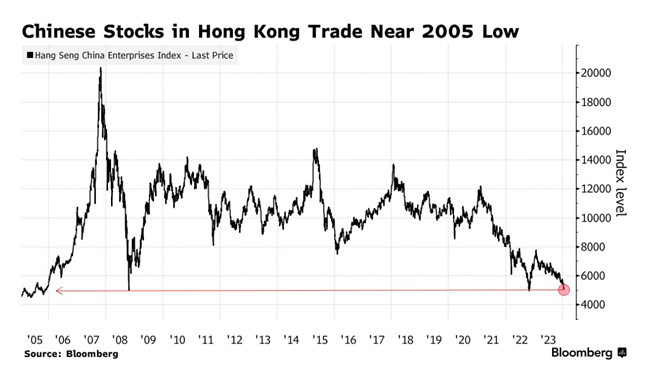

Remember in 2007-08 when bulls were all in love with China and projecting endless growth and outsized investment returns as far as the eye can see? It turns out the business cycle was not repealed, and high valuations and euphoric consensus remain a reliable precursor to mean reversion and capital losses. Chinese stock prices have lost money in the 16 years since 2007 and are now back near 2005 levels. See Hong Kong stocks at 36% discount show the actual depth of China gloom:

See Hong Kong stocks at 36% discount show the actual depth of China gloom:

The steeper losses in Hong Kong, where some of China’s most influential and innovative firms are listed and Beijing’s interference is less felt, paint a more worrisome picture of global investor sentiment toward the world’s No. 2 economy. Signs of government intervention to prop up the mainland market have increased in recent weeks as selling pressure continued despite a more optimistic Wall Street, where the S&P 500 Index climbed to a record on Friday.

A confluence of factors has been behind the seemingly endless selloff in Chinese shares, ranging from a deepening housing slump to stubborn deflationary pressures, as well as uncertainties about the trajectory of US interest rates. Chinese commercial lenders’ latest move to keep their benchmark lending rates unchanged, which followed the central bank’s recent decision to maintain borrowing costs, may also have disappointed investors hoping for more aggressive stimulus.

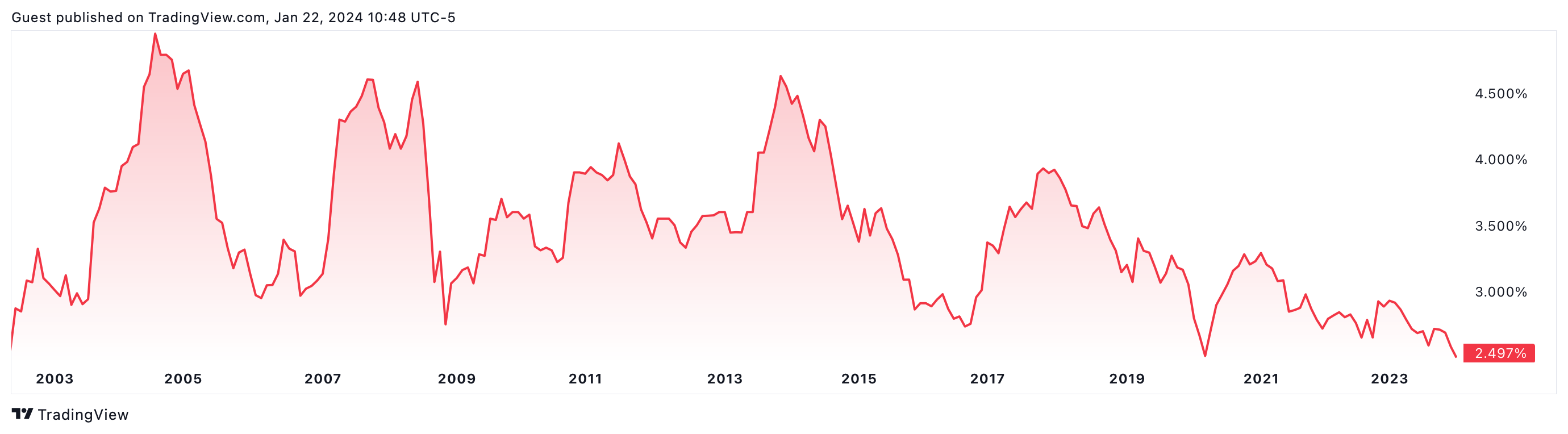

Chinese treasury bonds have rallied sharply as beaten-up capital capitulates out of riskier markets and back to the relative safety of government bonds. The Chinese 10-year Treasury (prices shown below since 2002) is yielding 2.49% this morning, a low last seen in April 2020 and 2008 before that. It’s as if the credit-driven inflation boom never happened, except for all the remaining debt, overcapacity and excess inventory that remains. Excess supply is a deflationary force globally as China marks down export prices and imports less. In December, Chinese steel output fell 15% year-over-year to the lowest level in 15 years.

It’s as if the credit-driven inflation boom never happened, except for all the remaining debt, overcapacity and excess inventory that remains. Excess supply is a deflationary force globally as China marks down export prices and imports less. In December, Chinese steel output fell 15% year-over-year to the lowest level in 15 years.

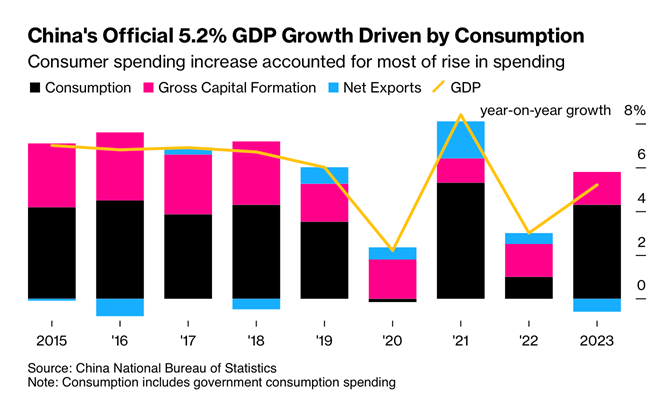

China has grown old and heavily indebted faster than its masses could become middle class. By 2022, household consumption drove just 37% of China’s GDP, its lowest level since 2014. With net exports (in blue below since 2015) and capital investment weak (in pink), household consumption (in black) is not able to pick up the economic slack. China’s $18 trillion economy is the second largest globally, accounting for just over 17 percent of global GDP in 2023, compared with 25% for the United States (World Bank data). It will take some time for other economies to fill the China void.

China’s $18 trillion economy is the second largest globally, accounting for just over 17 percent of global GDP in 2023, compared with 25% for the United States (World Bank data). It will take some time for other economies to fill the China void.