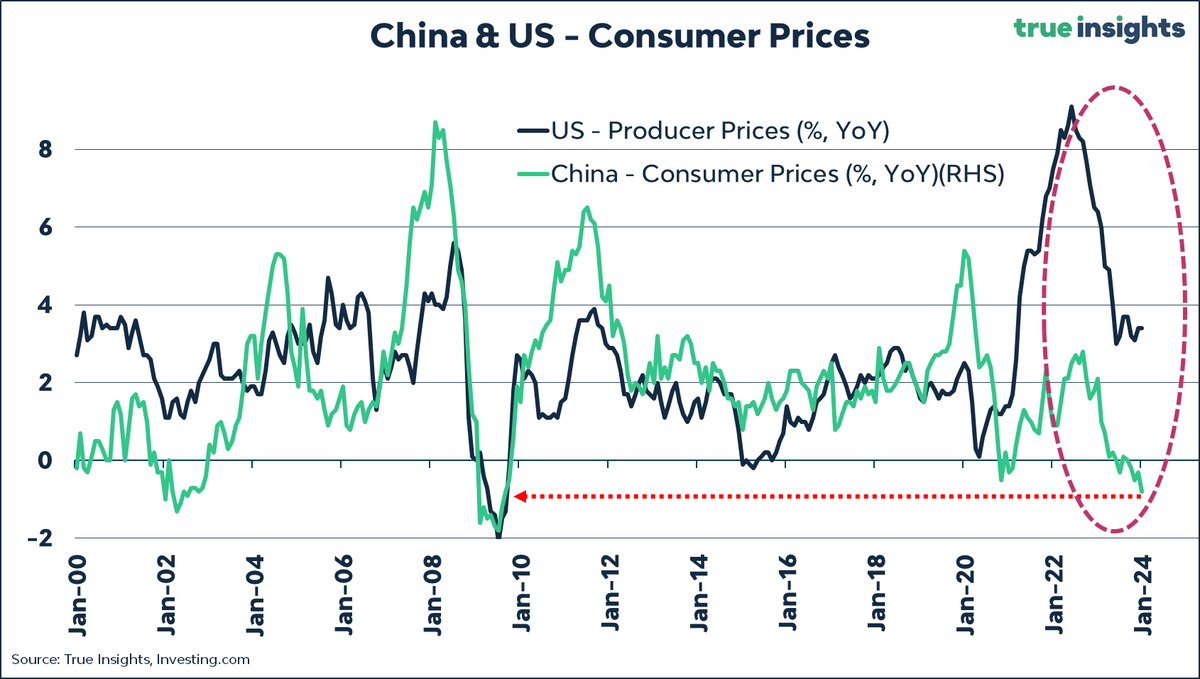

Since China entered the World Trade Organization in December 2001, US producer prices (black line below since 2000) have tracked up and down with China’s Consumer Price Index (CPI in green). Awash in excess capacity today, China is exporting deflationary pressures to the rest of the world.

In several key manufacturing sectors, goods are selling at less than cost, crushing suppliers in other countries as well as at home. See, Chinese chip-related companies shutting down at record speed:

In several key manufacturing sectors, goods are selling at less than cost, crushing suppliers in other countries as well as at home. See, Chinese chip-related companies shutting down at record speed:

These firms are not just struggling with sales. Most are losing money from unsold stock, due to market oversupply and a general downturn in the semiconductor industry from wider economic circumstances. A big part of the problem comes from a misstep in planning: In 2021 and 2022, many companies produced tons of chips, expecting high sales from the Covid-induced work-from-home trend. But as the pandemic waned, demand took a downturn and the market slumped in the end of 2022 / beginning of 2023, leaving companies with a lot of inventory they couldn’t sell. And, of course, these products are losing value as time passes.

Also see, With Solar Industry in Crisis, Europe in a bind over Chinese imports and China is Oversupplied with Commodities as Deflation Shifts:

China’s commodities markets are heading into the Lunar New Year break on a glum note, with deflation embedded on both the consumer and producer sides of the economy…

Weak aggregate demand is the central issue for policymakers, but ample supply is prevalent across a number of commodities markets…

Much depends on how demand shapes up once China’s construction season begins anew in March, and whether fiscal stimulus will continue to effectively counter steep declines from the crash in the metals-intensive housing market.

Last but not least are the deflationary impacts of weakness compounding from the Chinese property sector, see China’s property crisis is starting to spread across the world:

Now, a new batch of overseas assets acquired in a decade-long Chinese expansion spree are starting to hit the market as landlords and developers decide they want cash now to shore up domestic operations and pay off debts — even if that means taking a financial hit. Beijing’s crackdown on excessive borrowing has left few developers unscathed, even those once considered major players. A unit of Guangzhou-based China Aoyuan Group Ltd., for example, which is in the middle of a $6 billion debt restructuring plan, sold a plot in Toronto at about a 45% discount to the 2021 purchase price late last year, according to data provider Altus Group.

“With motivated sellers, the market freeze could thaw, improving transparency and price discovery,” said Tolu Alamutu, a credit analyst at Bloomberg Intelligence. “Portfolio valuations may have further to fall.”

Independent China analyst Leland Miller offers some context on the likelihood of policy responses in the discussion below.

China Beige Book CEO Leland Miller explains why China’s real estate sector meltdown and stock market rout are not going to influence the country’s authorities to stray from long-term security and economic goals. Leland speaks with Tom Keene and Paul Sweeney on Bloomberg Radio. Here is a direct video link.