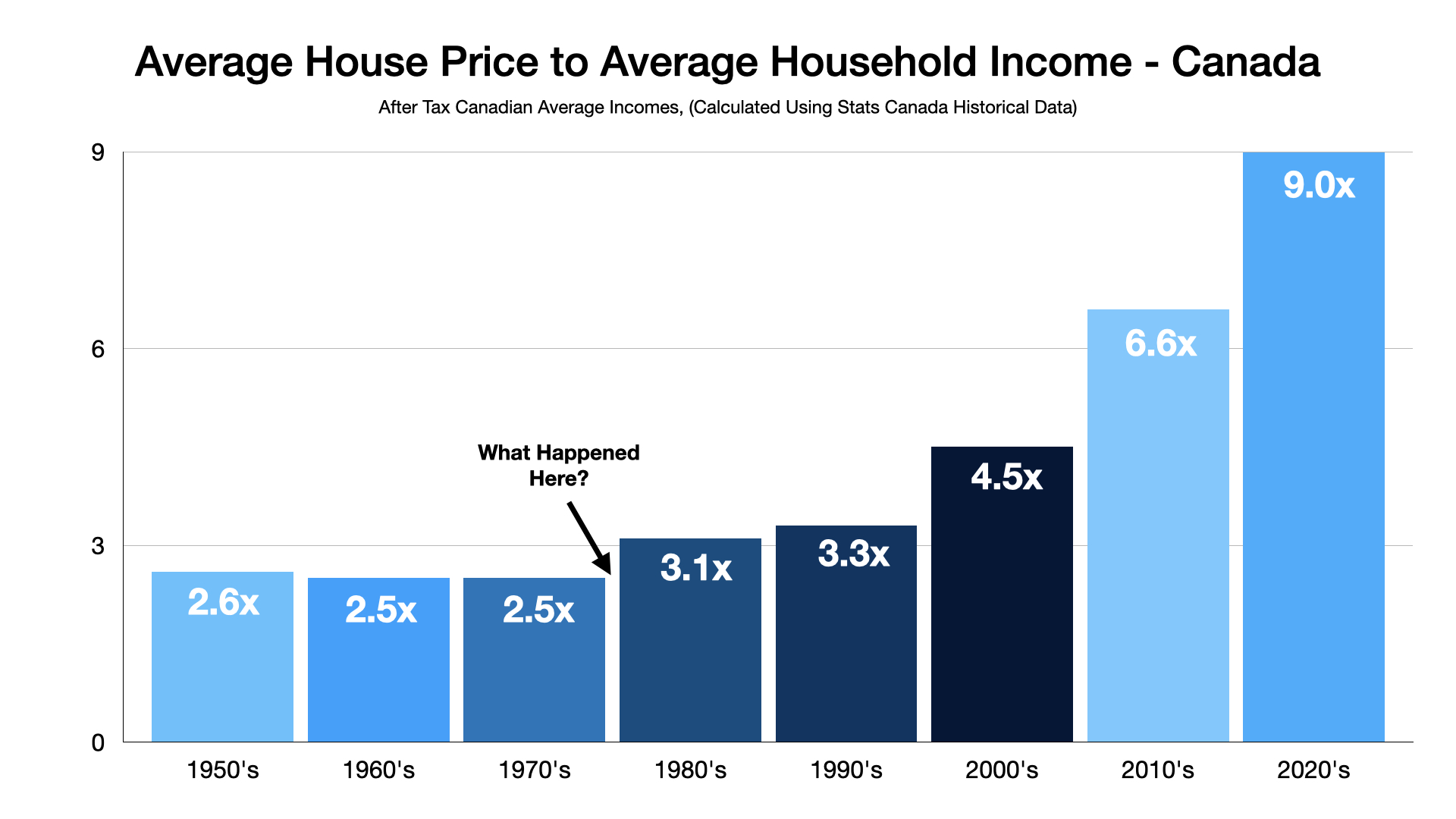

The results of the easy money experiments from 2009 to 2022 are widely evident: they yielded record indebtedness and unaffordable housing. This was especially true in Canada, where the median household debt to income was 175% in the second quarter of 2024 from 156% in the fourth quarter of 2008. At the same time, the average home price soared from 3.3x the average household income in the 1980s to an impossible 9x since 2020 (the source for the chart below is unknown). The US median home price, at 7.2x the median household income, also touched a new all-time high in September, above the 7.1x recorded in 2022 and 6.8x at the peak of the 2006 housing bubble (chart below since 1945 courtesy of The Kobbeissi Letter). Home prices soared 50% in the last five years, nearly 3x the 17% growth in household income.

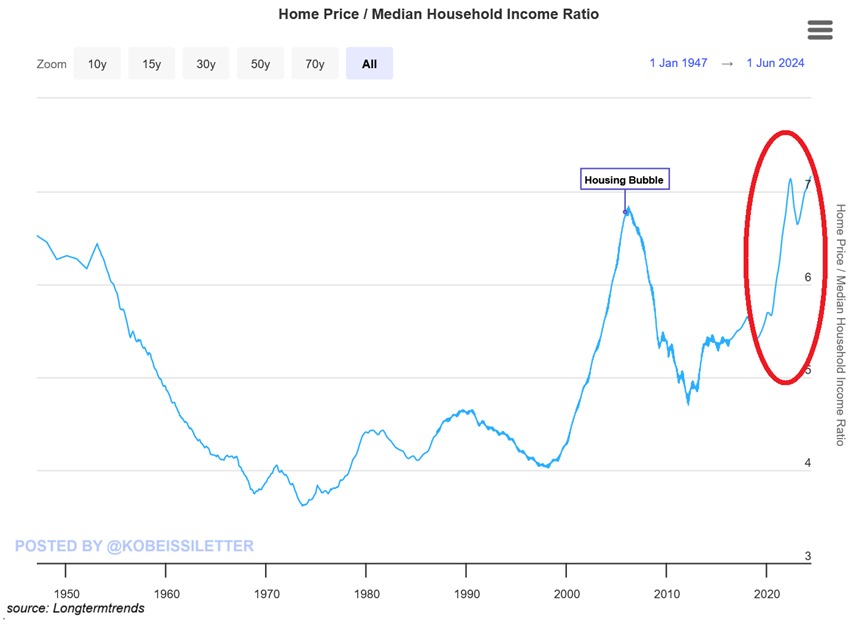

The US median home price, at 7.2x the median household income, also touched a new all-time high in September, above the 7.1x recorded in 2022 and 6.8x at the peak of the 2006 housing bubble (chart below since 1945 courtesy of The Kobbeissi Letter). Home prices soared 50% in the last five years, nearly 3x the 17% growth in household income.

Statistics Canada reported last week that the gap in the share of disposable income between the wealthiest two-fifths of Canadians and the bottom two-fifths grew to 47 percentage points in the second quarter of 2024—the widest gap since StatsCan first started collecting such data in 1999.

Statistics Canada reported last week that the gap in the share of disposable income between the wealthiest two-fifths of Canadians and the bottom two-fifths grew to 47 percentage points in the second quarter of 2024—the widest gap since StatsCan first started collecting such data in 1999.

While the lowest 20% of income earners saw a slight rise in their share of disposable income due to wage increases, the middle 60% saw a decrease.

In the second quarter, the top 20% of Canadians held more than 66% of the country’s wealth, averaging $3.4 million per household. By comparison, the bottom 40% of Canadians accounted for only 2.8% of Canada’s wealth.

StasCan noted that the extreme wealth gap driven by the top 20% of income earners was mainly due to investment gains attributed to higher interest rates. See October 10 Statscan Report:

While higher interest rates can lead to increased borrowing costs for households, they can also lead to higher yields on saving and investment accounts. Lower income households are more likely to have a limited capacity to take advantage of these higher returns, as on average they have fewer resources available for saving and investment.

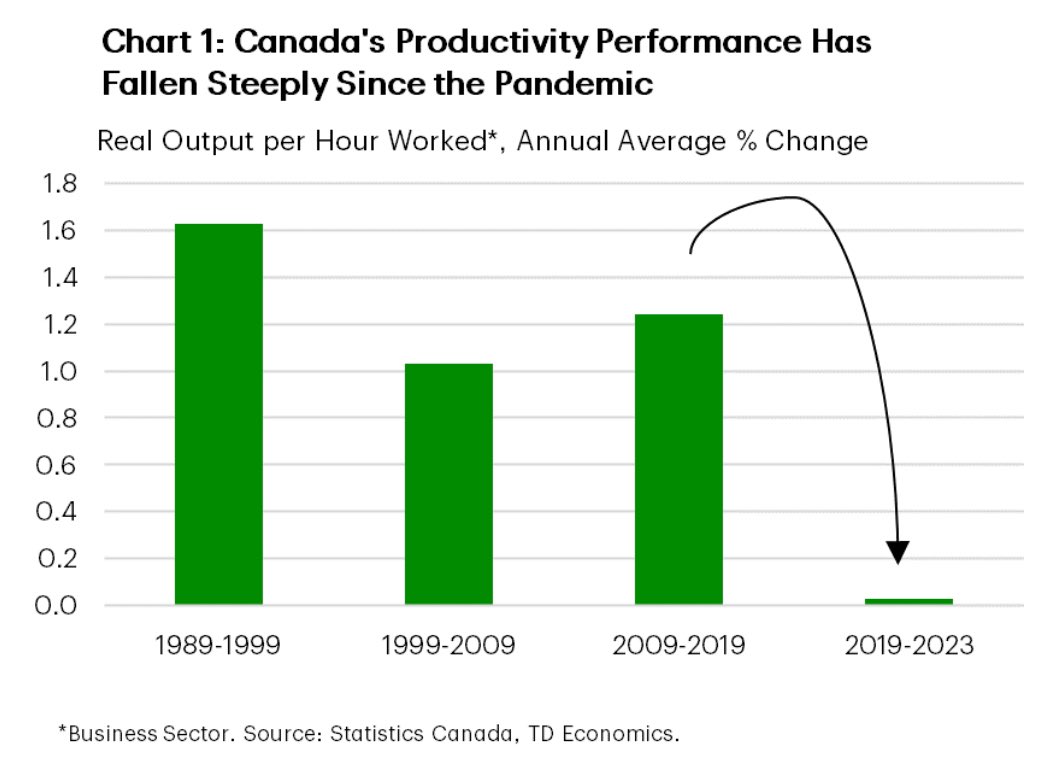

Higher interest rates incentivize saving and rational investment while discouraging speculation, asset bubbles and excessive counter-productive consumption. The collapse in Canadian productivity (below since 1989) undermines our standard of living and demands attention.

As cries build for central banks to slash policy rates back near the lows and governments to resume “free” money handouts, sober analysis begs to differ.

As cries build for central banks to slash policy rates back near the lows and governments to resume “free” money handouts, sober analysis begs to differ.