On September 18, the US Fed cut its overnight target rate by 50 basis points (bps), and risk markets went wild. Stock and corporate debt prices have risen to more all-time highs, and real estate bulls rejoice that lower interest rates will reignite loan demand and save highly leveraged property markets.

The trouble is that central banks don’t control fixed-term loan rates. The Treasury market sets those, and the Treasury market hasn’t been cooperating.

From 3.93% in mid-October, the US 30-year Treasury yield rose 54 bps to 4.47% yesterday, pushing 30-year US mortgage rates to 6.8% from 6.1% in September (and 2.7% at the low in 2021). Not surprisingly, US mortgage applications fell 17% in the second week of October—the sharpest weekly contraction since 2015 (outside of early 2020 during the pandemic). Sale prices registered month-over-month declines in ten US states (Reventure data).

In Canada, the Bank of Canada has lowered its overnight rate from 5% to 4.25% and is expected to deliver another 50 bp rate cut tomorrow (some are calling for 75bps).

So far, Canada’s 5-year Treasury bond yield has risen from 2.69% on September 16 to 3.01%, and Canada’s fixed-term mortgage rates have moved back above 4% (from less than 2% during the early pandemic).

Most Canadian realty markets are stagnant. Some are downright dead: new condo sales in the Greater Toronto and Hamilton area (all the rage during the easy-money mania) hit a near 3o-year low in the third quarter with volumes -63% year-0ver-year.

The median Canadian home sale price in September was $669,630, down 20% from $835K at the manic peak in February 2022. Nationally, new listings are up 16.8% year-over-year. See CREA lowers housing market forecast for 2024 amid a ‘holding pattern’ for home sales.

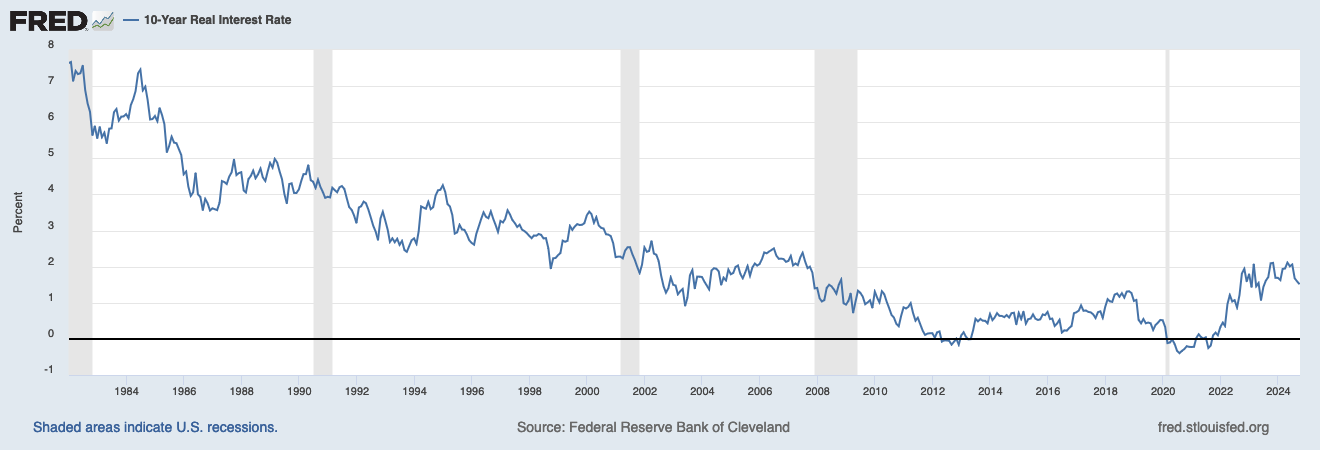

Despite central bank rate cuts, real interest rates (nominal minus inflation) remain near the highest since 2008 (US 10-year real rates below since 1980). High real yields are great for savers but not for the indebted masses, and the world economy has never been more indebted than today.

High real yields are great for savers but not for the indebted masses, and the world economy has never been more indebted than today.

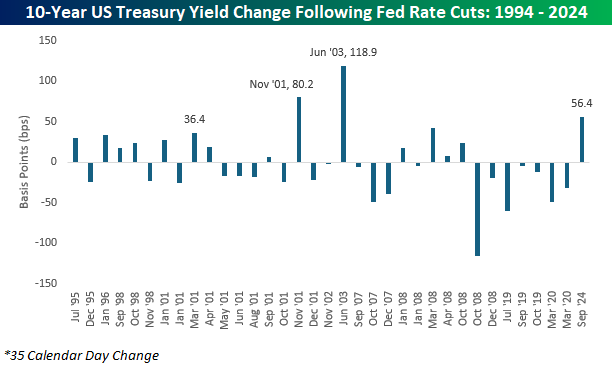

As I’ve noted many times, it’s been typical for risky assets to celebrate when the US Fed starts easing and for Treasury prices to initially drop (yields to jump) as they do.

The 56bp increase in the US 10-year Treasury yield since September 18 is, so far, the third largest following the first Fed cut since 1995 (chart below, courtesy of Bespoke Investments). In every case, the initial yield back-up was short-lived before spreading economic strife led to a sell-off in risky assets, a flight to safety, and a rebound in Treasury prices (lower yields) as central banks continued slashing overnight rates throughout.  The trouble with central bank rate cuts is that they come too little, too late. It is too late to save those who took on too much debt and overpaid for assets during the easy money mania, and it is too late to stop recessions and asset bubbles from popping in their usual course.

The trouble with central bank rate cuts is that they come too little, too late. It is too late to save those who took on too much debt and overpaid for assets during the easy money mania, and it is too late to stop recessions and asset bubbles from popping in their usual course.