During the financial mania of 1634 to 1637, people bid up the price of tulip bulbs. At peak craziness, a “Semper Augustus” bulb sold for the equivalent value of a $14,000,000 mansion on the Amsterdam Grand Canal today. Then the fever broke, dragging bulbs and participants’ net worth back into the dirt.

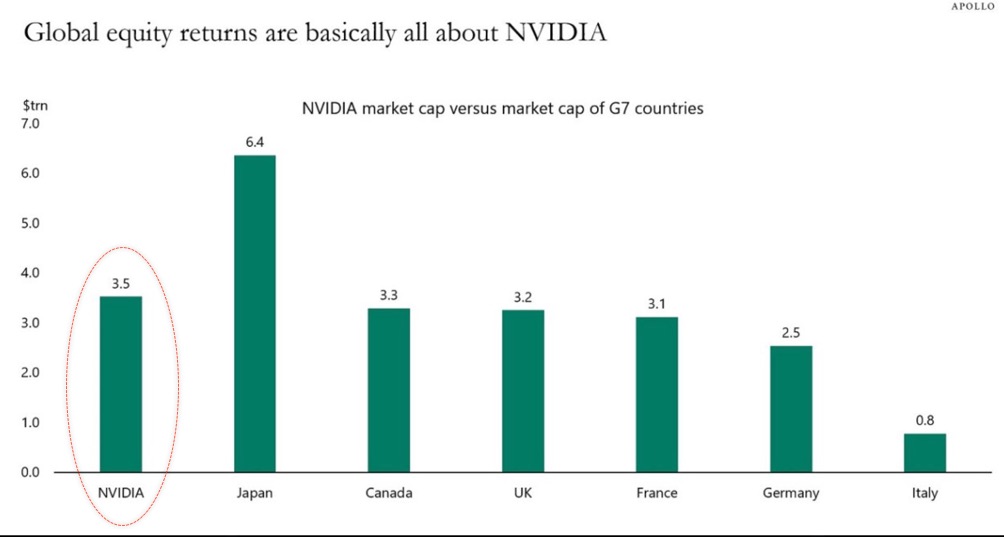

Today’s financial mania has been inspired by artificial intelligence. At $3.3 trillion, the market valuation of one chip maker, NVIDIA, has been bid above the entire stock market of five G7 countries: Germany, Italy, France, the U.K. and Canada (chart below courtesy of Apollo).  Let that sink in for just a second. NVIDIA is priced more than all the publicly traded companies in Italy and Germany combined. A price-to-sales ratio above three and price-to-earnings above 20 are considered high-risk valuations for growth companies. NVIDIA has a price-to-sales ratio above 36 and a price-to-earnings ratio above 64. Even Apple is trading at a price-to-sales level above nine and a price-to-earnings level above 35.

Let that sink in for just a second. NVIDIA is priced more than all the publicly traded companies in Italy and Germany combined. A price-to-sales ratio above three and price-to-earnings above 20 are considered high-risk valuations for growth companies. NVIDIA has a price-to-sales ratio above 36 and a price-to-earnings ratio above 64. Even Apple is trading at a price-to-sales level above nine and a price-to-earnings level above 35.

Over the past year, S&P 500 forward earnings per share estimates have risen 4% while the index’s price has risen ten times as much. The five-point multiple expansion for the S&P 500 from last October’s 17x forward earnings to today’s 22x is a very rare two-standard deviation event. And yet, 51.4% of consumers surveyed expect stock prices to rise further over the next year—the most since 1987.

The six most expensive S&P 500 companies are all in the tech sector (see below) and now account for a record 28.8% of the index market cap. When the fever breaks and growth is revalued, the entire stock market will be up for adjustment.

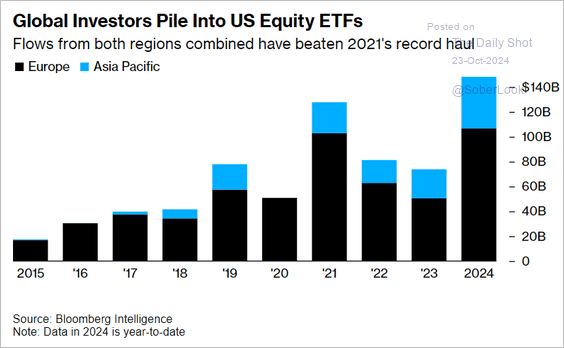

Value-indiscriminate buying has become an international pastime. Global participants have piled record amounts into US equity exchange-traded funds in 2024, surpassing even the prior record seen in 2021 (ETF inflows below since 2015, via The Daily Shot).

Value-indiscriminate buying has become an international pastime. Global participants have piled record amounts into US equity exchange-traded funds in 2024, surpassing even the prior record seen in 2021 (ETF inflows below since 2015, via The Daily Shot).

Starting valuations are reliably predictive of longer-term investment returns, and there is presently no compensation on offer for taking equity risk in portfolios.

The 3.66% S&P 500 earnings yield is 58 basis points less than the US 10-year Treasury yield, at 4.24%. Even the optimistic 4.4% earnings yield forecast for the fourth quarter of 2025 is a pathetic 26 basis points of equity risk premium from here.

Today’s equity risk premium is at the 15th percentile of a 100-year distribution, meaning stocks have rarely been more expensive (see chart below since 1925, courtesy of UBS) and are priced to underperform Treasury bonds from here.

Corporate credit markets are no better, with high yield spreads of just 285 basis points over similar-dated Treasuries—the least risk compensation offered since mid-2007 (as shown below since 1995).

Corporate credit markets are no better, with high yield spreads of just 285 basis points over similar-dated Treasuries—the least risk compensation offered since mid-2007 (as shown below since 1995).

More than 60% of so-called ‘investment’ flows today are funnelled into ETFs and pools that track stock indexes without regard for real-life loss and return probabilities—autonomous vehicles with no drivers at the wheel.

Several times in the past 24 years, we have seen how quickly indiscriminate buying morphs into indiscriminate selling when the crowd’s sentiment sours. The risks are higher when older people are betting because they have less time to grow back losses and less ability to work longer. See America’s Retirees are Investing more like 30-year-olds:

Older Americans keep rolling the dice in the stock market, ignoring the conventional wisdom to protect their nest eggs by shifting more of their investments to bonds.

Nearly half of Vanguard 401(k) investors actively managing their money and over age 55 held more than 70% of their portfolios in stocks. In 2011, 38% did so. At Fidelity Investments, nearly four in 10 investors ages 65 to 69 hold about two-thirds or more of their portfolios in stocks.

And it isn’t just baby boomers. In taxable brokerage accounts at Vanguard, one-fifth of investors 85 or older have nearly all their money in stocks, up from 16% in 2012. The same is true of almost a quarter of those ages 75 to 84.

Fiduciaries are given the weighty responsibility of trying to protect life savings from foreseeable losses. But there are very few of us around. Financial commentary is overwhelmingly dominated by salespeople, finance writers, and podcasters talking about ‘how to play’ capital flows like crap tables at a casino. They take credit for wins but never for losses. Many use media to herd the public in and out of positions that benefit the speaker.

Gambling can feel fun while slots payout, but rational minds know that good luck never continues indefinitely. The serious question for each of us to answer is: How much of our savings can we afford to lose? What’s the right amount of capital to bet at a casino? If we aren’t asking ourselves these questions, we don’t understand the game.