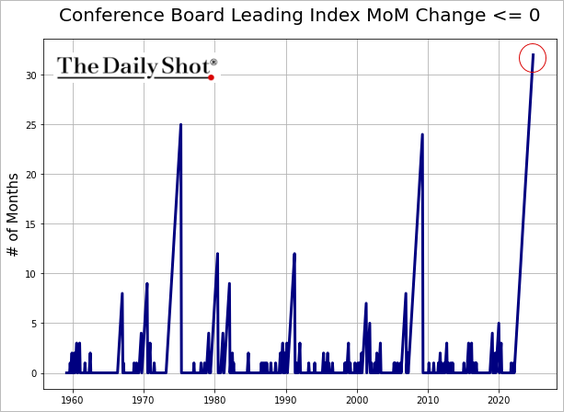

This week, we learned that the US index of leading economic indicators (Conference Board LEI) contracted to 99.5 in October—the 32nd consecutive month of contraction and the longest since at least 1957 (all shown below courtesy of The Daily Shot).

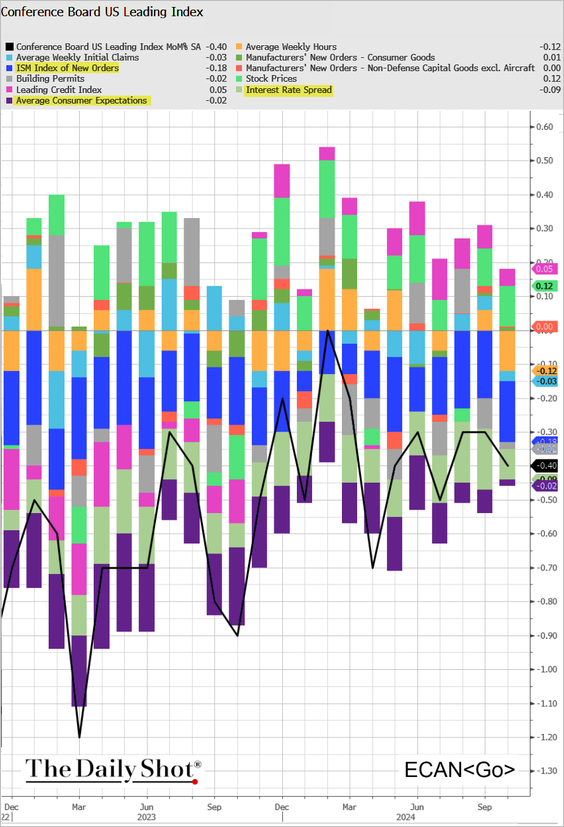

The only LEI items that expanded in October were stock (green) and credit (pink) prices.

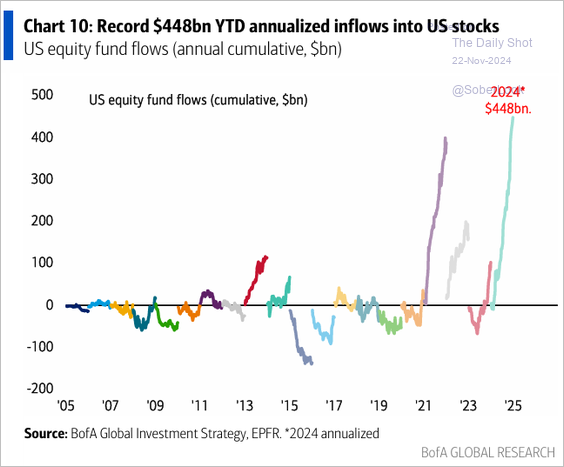

The only LEI items that expanded in October were stock (green) and credit (pink) prices.  But who needs economic strength when risk markets are jubilant. Tech-heavy US equity funds have continued attracting record global inflows year to date.

But who needs economic strength when risk markets are jubilant. Tech-heavy US equity funds have continued attracting record global inflows year to date.

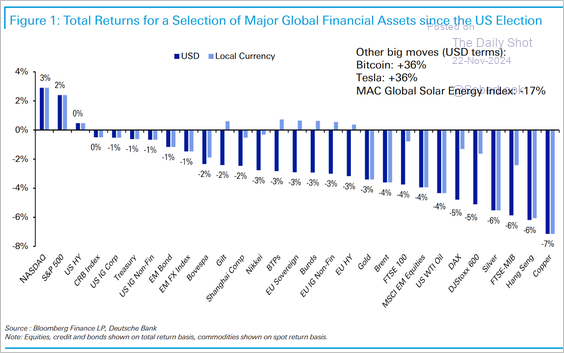

Since the US election, Bitcoin and Tesla shares have surged about 36%. Other global markets and assets have seen capital outflows (below since the election), which has helped the US dollar index (DXY) move above 107—the highest since November 2022.

Since the US election, Bitcoin and Tesla shares have surged about 36%. Other global markets and assets have seen capital outflows (below since the election), which has helped the US dollar index (DXY) move above 107—the highest since November 2022.  Chip leader NVIDIA, with a market capitalization (shares x price) of $3.6 trillion, trading more than 32 times expected 2025 sales, now accounts for 7% of the S&P 500 price. The top 7 most expensive companies–all in the tech space–account for just over 30% of the index value (as shown below). Rarely has the fate of so many depended on the continued euphoric pricing of so few.

Chip leader NVIDIA, with a market capitalization (shares x price) of $3.6 trillion, trading more than 32 times expected 2025 sales, now accounts for 7% of the S&P 500 price. The top 7 most expensive companies–all in the tech space–account for just over 30% of the index value (as shown below). Rarely has the fate of so many depended on the continued euphoric pricing of so few.

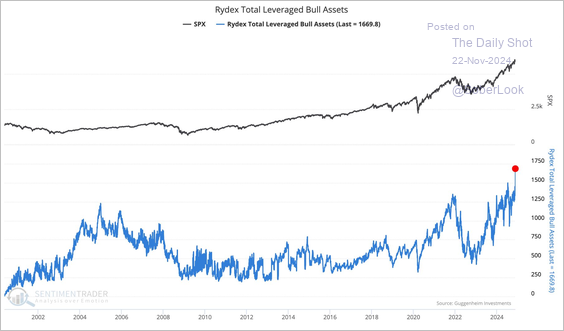

Further magnifying risk exposure, assets in leveraged security funds (blue line below since 2001, with S&P 500 in black) have taken out the 2022 peak.

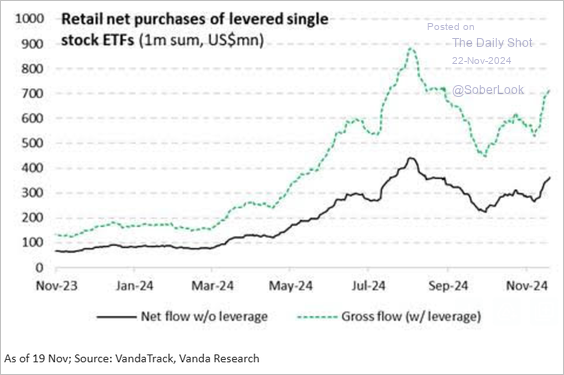

Further magnifying risk exposure, assets in leveraged security funds (blue line below since 2001, with S&P 500 in black) have taken out the 2022 peak. A retail offering of levered single-stock funds is a new weapon of mass destruction to magnify the downside from here (green line below since November 2023).

A retail offering of levered single-stock funds is a new weapon of mass destruction to magnify the downside from here (green line below since November 2023).

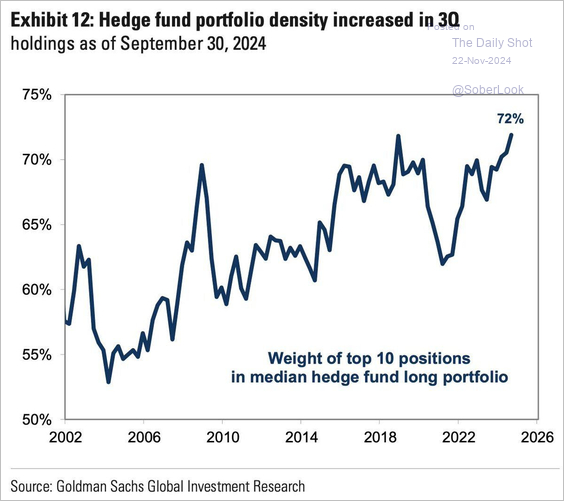

Hedge funds also had a median 72% of their long holdings concentrated in 10 stocks in September, the highest since 2019 and 2000 (shown below since 2002).

Hedge funds also had a median 72% of their long holdings concentrated in 10 stocks in September, the highest since 2019 and 2000 (shown below since 2002).

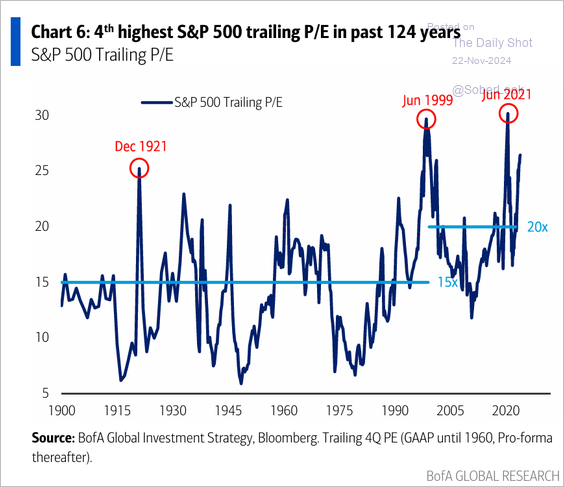

The latest narratives around AI, central banks’ omnipotence, and Trump’s promises have once more convinced the masses that the price is irrelevant. The S&P 500, trading at 24x estimated forward earnings, is the fourth-highest multiple since 1900 (as shown below), and all prior incidents ended in widespread financial pain.

The latest narratives around AI, central banks’ omnipotence, and Trump’s promises have once more convinced the masses that the price is irrelevant. The S&P 500, trading at 24x estimated forward earnings, is the fourth-highest multiple since 1900 (as shown below), and all prior incidents ended in widespread financial pain.  In April 2004, just after the 2000-03 stock bubble implosion, behavioural finance pioneer Daniel Kahneman gave an interview where he identified common mistakes investors make (thanks to Dennis Gartman for reminding me of it this morning).

In April 2004, just after the 2000-03 stock bubble implosion, behavioural finance pioneer Daniel Kahneman gave an interview where he identified common mistakes investors make (thanks to Dennis Gartman for reminding me of it this morning).

Although Danny left us last March, his insights are timeless. See Clients Misbehavin’: An interview with Nobel Laureate Daniel Kahneman. Here are some interview highlights.

People mainly think of risk in terms of downside risk. They are concerned about the maximum they can lose. So that’s what risk means. In contrast, the professional view defines risk in terms of variance, and doesn’t discriminate gains from losses. There is a great deal miscommunication and misunderstanding because of these very different views of risk. Beta does not do it for most people, who are more concerned with the possibility of loss.

This is why individual investors typically will get in too late. By the time they convince themselves that everybody else is getting rich and they are the only ones not getting rich, it is probably late in the day. When those investors get in, it may be time for other people to get out. There is a psychological phenomenon that we are aware of which is that people see patterns in pure noise, where in fact there are no patterns at all. So people are prone to think that the world has changed, and they do not appreciate that the next turn is near.

During the bubble, there was some talk that the rules of the economy had been suspended, that we were in a new world where things can go straight up forever. Quite a few people almost believed that. We are very vulnerable to seeing random fluctuations as indications of permanent change, a new pattern.

The advisor is in a very difficult position, in that you want to do the best for your client but you also want to have clients. So it is a difficult world, but that’s the place we live in. The best advice may well be, “Do little and don’t think too much,” and “Leave it to me and don’t check your results too frequently because that will cause you to make mistakes,” but this advice can sound very self-serving. For good advice to be acceptable, we are dependent on the public getting educated.