Professor Robert Shiller came to fame when he published his book Irrational Exuberance in 2000 warning that the stock market had become a bubble which could lead to a sharp decline. In response, he has described how stock-loving little old ladies, and others, verbally assaulted him for his bearish tones on his speaking tour that year.

In 2005 as the US realty market was entering a Fed-enabled bubble of its own, Shiller again warned that double digit price rises could not outstrip inflation long term because, except for land restricted sites, price increases have tended to be constrained by the rate of wage inflation over time. In 2006 he wrote: “there is significant risk of a very bad period, with slow sales, slim commissions, falling prices, rising default and foreclosures, serious trouble in financial markets, and a possible recession sooner than most of us expected.” Comments like these are fighting words in Canada, Australia, Britain and other debt-fueled hot spots today, to be sure.

Over the past 5 years, as repeated Central Bank interventions and stock buy-backs elongated the current market cycle years beyond the global manufacturing peak in 2011, Shiller has been more hesitant to warn about above-average asset valuations. (It is thought that his business ties to Standard & Poor’s and mainstream finance academia may also have become a subduing force in his commentary over the years.)

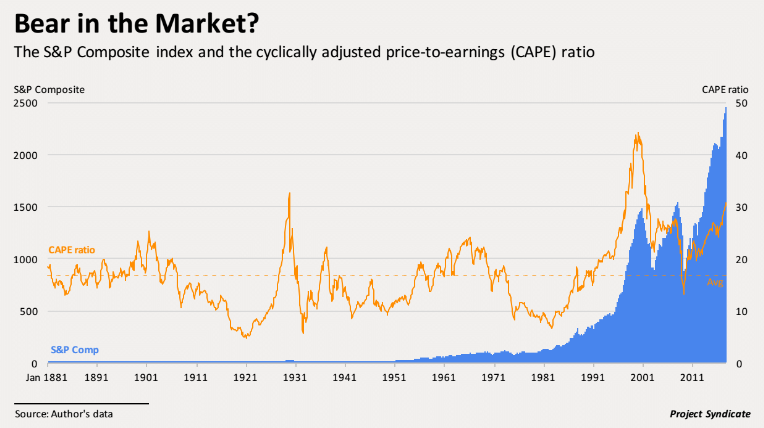

Still, his historically reliable cyclically adjusted price-to-earnings (CAPE) ratio (in orange below) versus the S&P 500 price index (in blue), speaks for itself, as shown here. Today it’s just one of the many historically reliable valuation measures screaming about capital risks in investment markets.

This week in Project Syndicate, Shiller ventured the most bearish article he has written in some time, see The U.S. stock market looks a lot like it did before most of the previous 13 bear markets.

And to all the long-always stock lovers who argue that a bear market can’t arrive because real earnings growth are double digit and volatility at record lows. Looking at data since 1881, Shiller bursts their narrative fallacy:

“…high growth does not reduce the likelihood of a bear market. In fact, peak months before past bear markets also tended to show high real earnings growth: 13.3% per year, on average, for all 13 episodes. Moreover, at the market peak just before the biggest ever stock-market drop, in 1929-32, 12-month real earnings growth stood at 18.3%.

Another piece of ostensibly good news is that average stock-price volatility — measured by finding the standard deviation of monthly percentage changes in real stock prices for the preceding year — is an extremely low 1.2%. Between 1872 and 2017, volatility was nearly three times as high, at 3.5%.

Yet, again, this does not mean that a bear market isn’t approaching. In fact, stock-price volatility was lower than average in the year leading up to the peak month preceding the 13 previous U.S. bear markets…before the 1929 crash, volatility was only 2.8%.

This is not to say that a bear market is guaranteed…

But my analysis should serve as a warning against complacency. Investors who allow faulty impressions of history to lead them to assume too much stock-market risk today may be inviting considerable losses.”