Over the past decade, record low interest rates and central bank-driven-speculation drove unprecedented global appetite for junky investment assets. As investment-grade yields fell from 5 and 6% to 1 and 2%, most individuals and pensions did not, or could not, increase their saving/contribution rates sufficiently to offset the loss of investment income. Even those who could have increased their contributions, mostly did not because they believed (hoped) that ‘higher yield’ (much higher risk) products were a solution. The financial sector, for its part, wanted to keep the dream of free-lunches alive, and not decrease its fee rates as yields fell, so it doubled down on selling the highest-fee products. Meanwhile, companies and individuals that could borrow more cheaply than ever before, did so with wild abandon.

Investors who were previously only comfortable in A-rated bonds migrated to BBBs, and those who were comfortable in BBBs moved to even lower quality. Moreover, as time went on, most did so with a higher percentage of their capital than ever before deemed prudent.

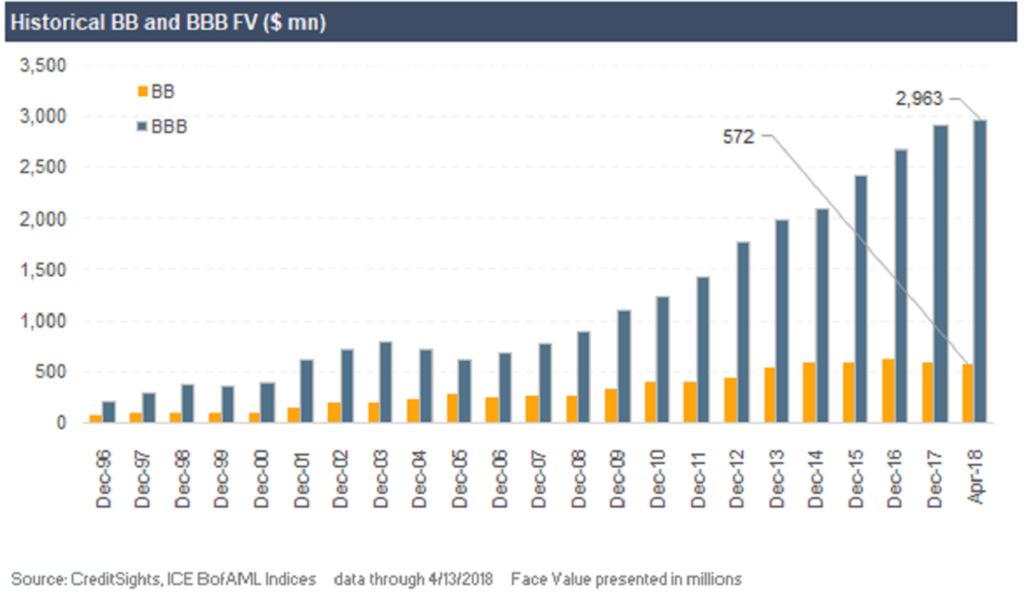

This chart of the mountain of non-investment grade debt (blue bars) issued since 2010 tells the tale.

Now as rates have risen and cash flows fallen, defaults have begun surging in typical late cycle patterns. Only this time, asset holders are more risk exposed, and have more to lose, than ever before. See: A $3 trillion dollar credit market has corporate bond investors on edge:

“We’re late in the credit cycle, and trying to figure out when everything turns,” said Erin Lyons, a senior credit strategist at New York-based research firm CreditSights Inc. “Some of these may eventually be downgraded.”

Notes in the lowest rungs above high-yield junk — in the BBB group from S&P Global Ratings or the Baa bucket from Moody’s Investors Service — total about $3 trillion, almost the size of Germany’s gross domestic product. The concern is that as rates rise it will cost companies more to roll over their obligations, and if earnings begin to slump as economic growth slows, that could blow out leverage ratios and lead to credit-rating cuts.

Not ‘could’ or ‘if’, just a matter of when–the turn has already started. During this part of the cycle, North American government bonds typically see ‘relative safe haven’ inflows.