Canada’s TSX stock index (which most Canadian funds and managers are designed to track up and down) peaked in September of the 1990 to 2000 expansion cycle. Then it crashed 50% over the next two years, recovered into June 2008, and crashed 50% a second time in the 2008-09 cycle. Though it rebounded into 2014, it’s had violent fits and starts since and has only managed to eke out a nominal capital gain of 1.95% annually over the last 19 years. A run-of-the-mill bear market loss of just 28% from here would return the TSX to its September 2000 top once more, and mark 20 years of a wild ride and zero capital gains.

Such is the secular bear game of snakes and ladders that we buy into from record valuations (knowingly or not).

Weighing in at 32%, Canadian financial companies are, by far, the most defining sector in the TSX. That’s risky concentration at the best of times, but especially coming off a ten-year expansion cycle during which earnings multiples have leapt, and Canadian households and businesses have taken on world-famous indebtedness.

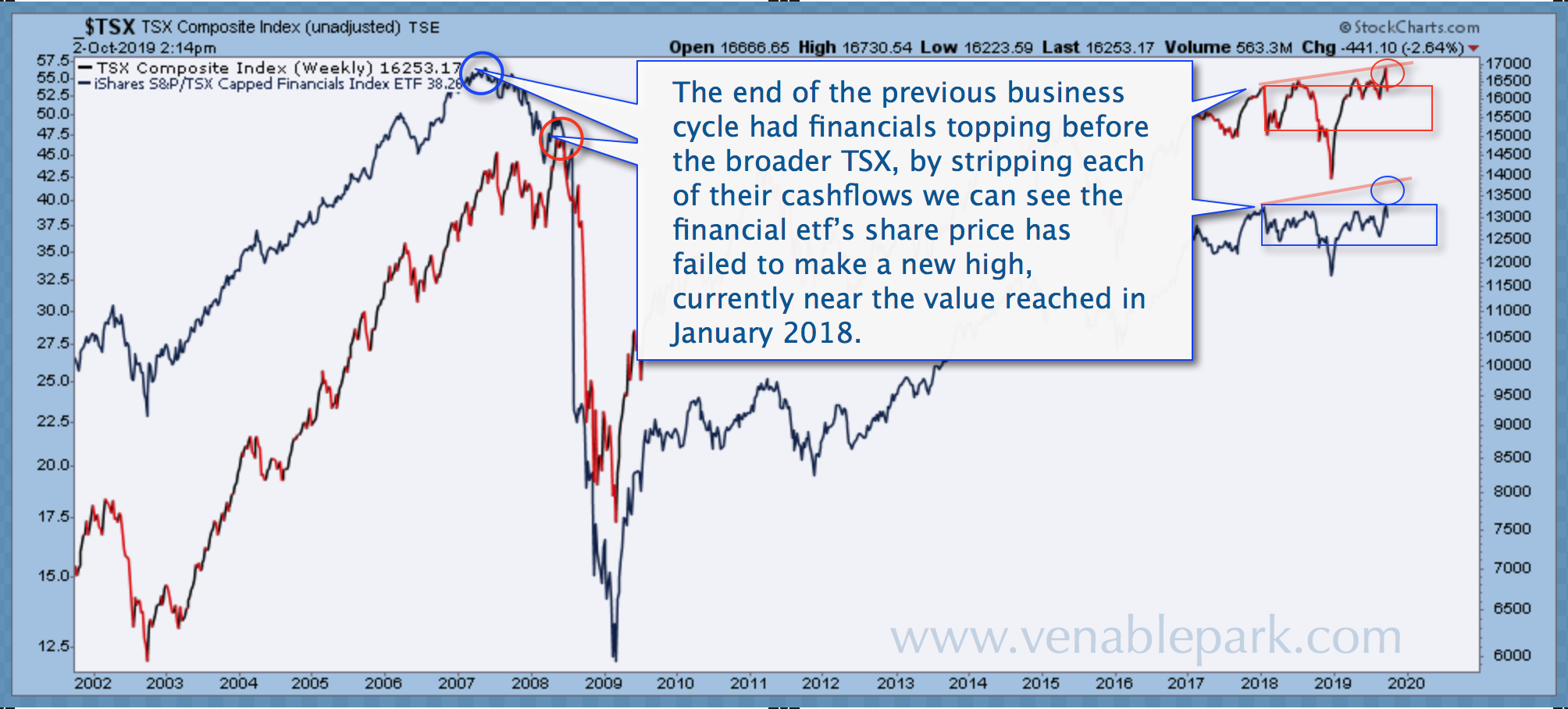

As shown in my partner Cory Venable’s ex-dividend chart below since 2002, financials (in blue) led the TSX (red) into the 2008 peak and 2009 bottom, then recovered and have remained range-bound since 2018 even as the TSX made a marginal new high in September.

In the sell-off over the last two days, financials have led, falling nearly a percent more than the TSX overall.

With defaults and insolvencies coming from below-average levels over the past decade and now rising across the country in both businesses and households, the banks are due for a ‘normalized’ period of higher losses. Years of quantitative easing extended the multiple expansion-debt-addition phase, and also magnified the bear market now looming for bank shares, the TSX, managers, funds and all the ETFs that track it.