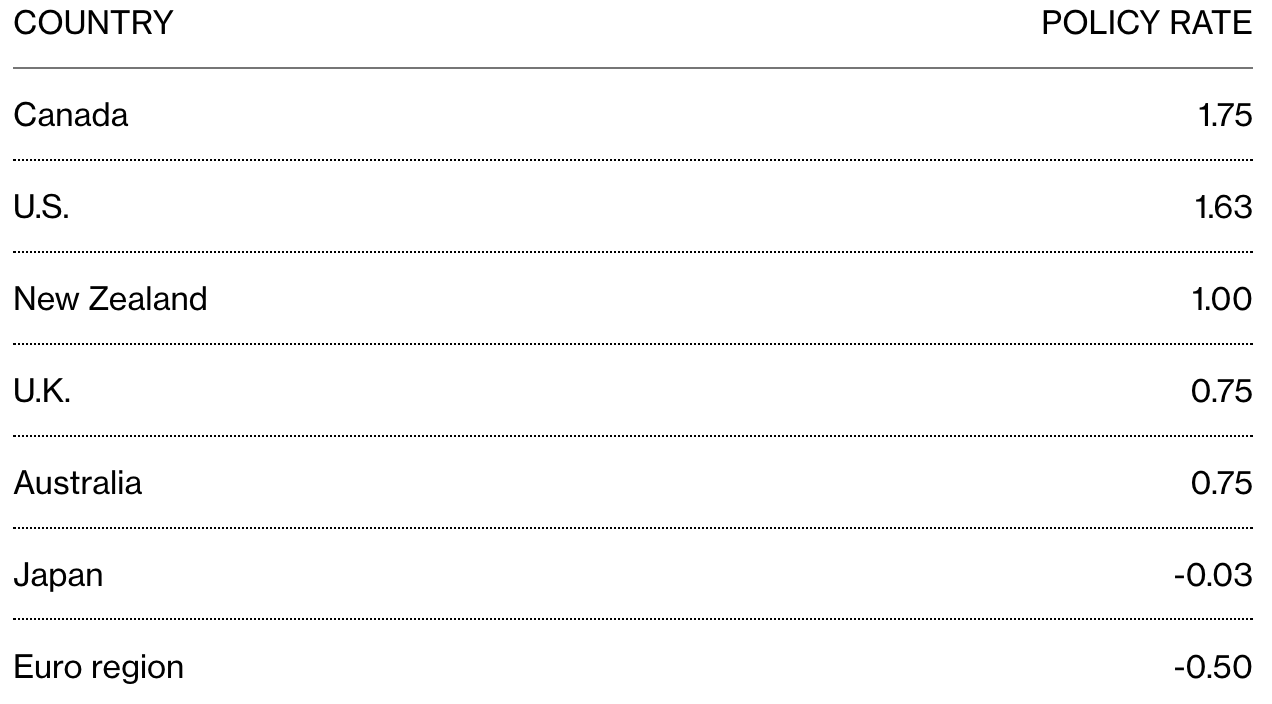

Yesterday, as expected, the Bank of Canada left its policy rate unchanged at 1.75% for the ninth consecutive meeting, even though other central banks have implemented dozens of rate cuts and liquidity injections over the last year in many countries. See Bank of Canada holds rate.

As a result, Canada’s overnight rate is now the highest among major trading partners (as shown below), even while the Canadian economy is forecast to grow at just 1.3% in the second half of 2019, and 1.7% in 2020.

As a result, Canada’s overnight rate is now the highest among major trading partners (as shown below), even while the Canadian economy is forecast to grow at just 1.3% in the second half of 2019, and 1.7% in 2020.

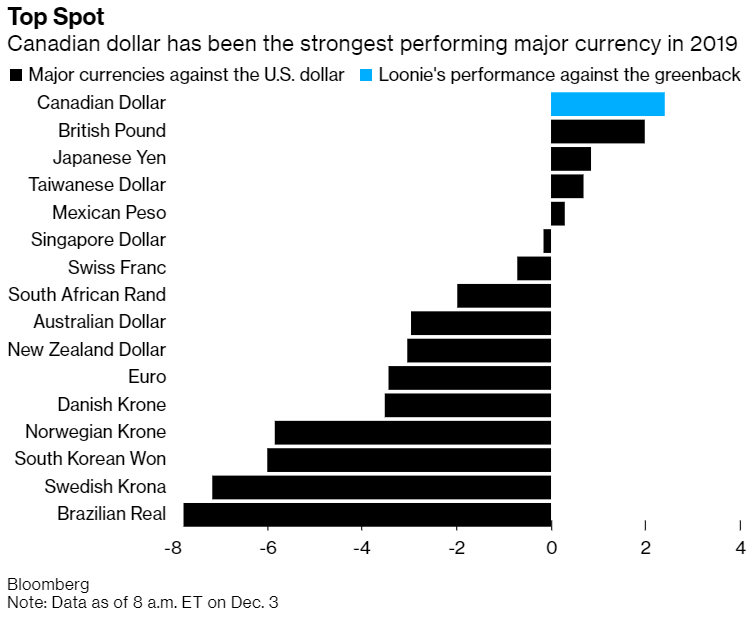

Canada is export-needy and our relative yield bonus is not helping that cause. Yield-hungry in-flows have helped buoy the loonie over the past year– 3% against the greenback– the best relative strength of all major currencies year to date (as shown below). With the domestic economy weak, Canada can’t afford currency strength for long.

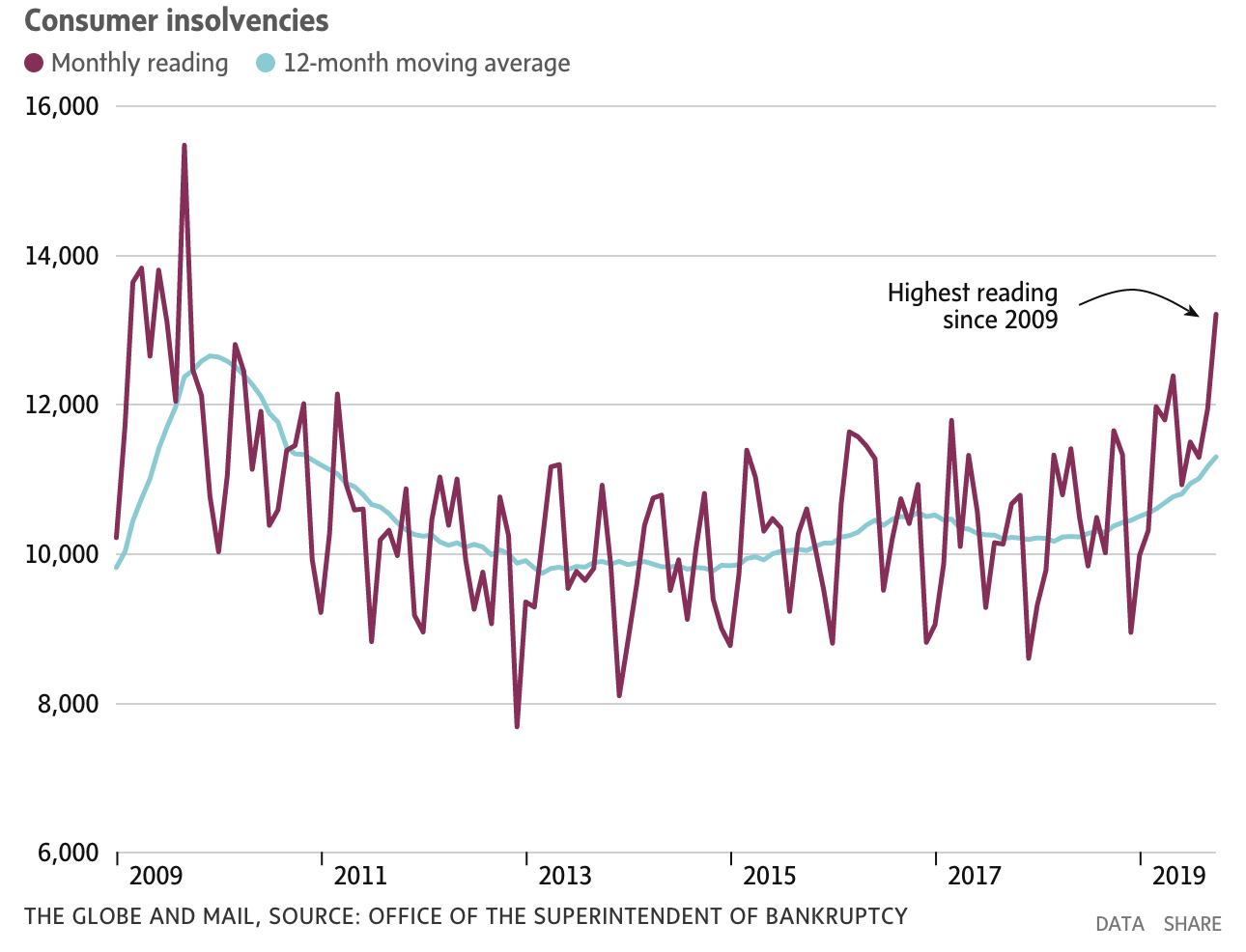

Policymakers would like a weaker buck to help boost Canadian exports, of course, but the Catch 22 is now at hand. A decade of low rates and credit abuse have already enabled record household debt (177% of disposable income). And Canadian insolvencies are leaping (as shown below since 2008), last month touching the highest level since the 2008-09 recession, even while lending rates remain historically low and employment rates, so far, near cycle highs. It’s alarming to model how defaults and losses will compound once layoffs accelerate and job openings shrink.

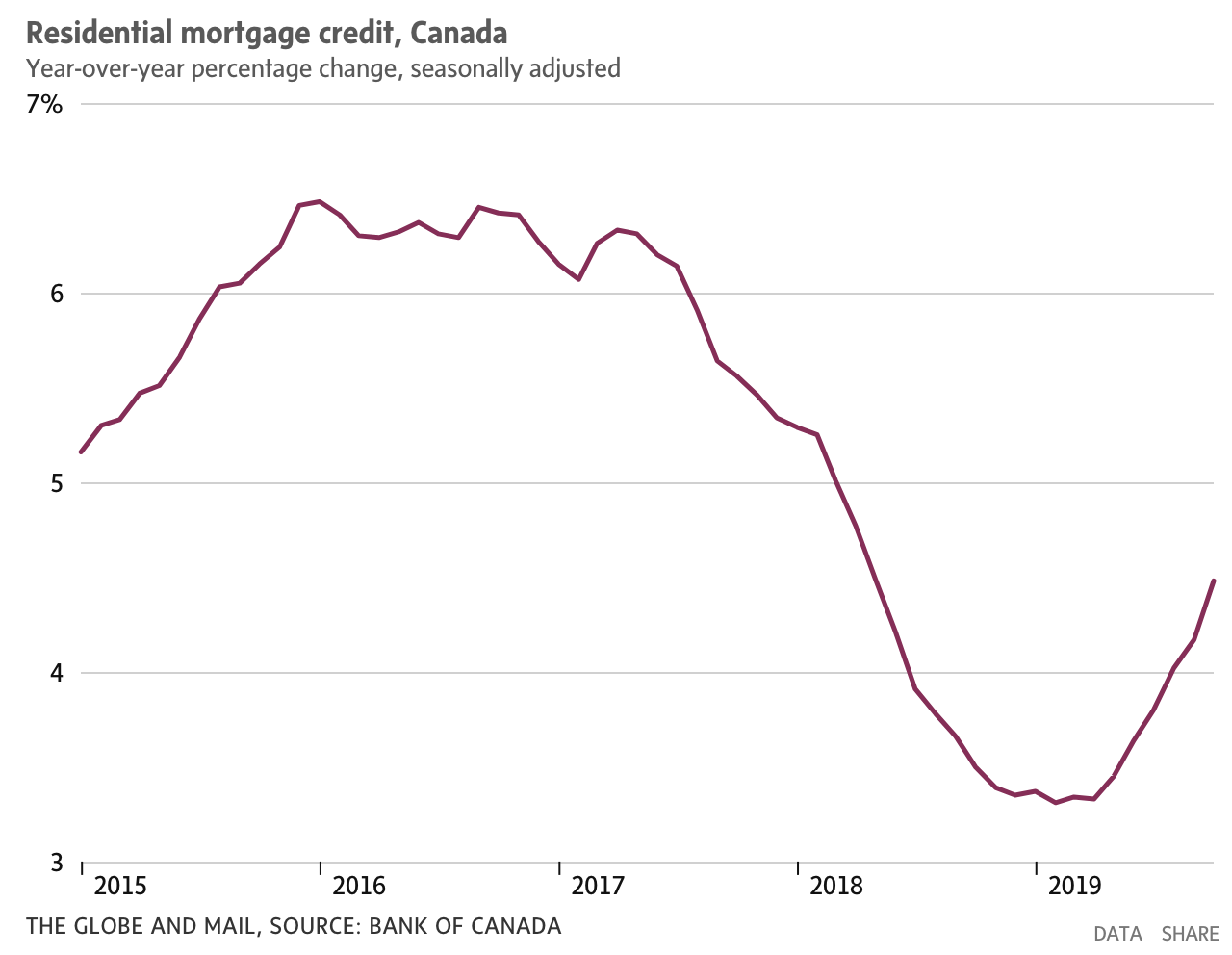

As I discussed last February, higher interest rates, tighter lending standards and speculation taxes in 2017 helped to begin a much-needed deflation in Canada’s housing bubble into early 2019, and the growth rate in residential mortgage credit mercifully halved (as shown below). But as weakness has permeated the global economy, and yield-seeking capital flows into Canadian government treasuries, their yields fall pushing Canadian mortgage rates down once more. Right on cue, borrowing has increased in 2019 at the fastest pace in a couple of years, escalating unaffordable housing and credit strains further.

Less than two percent above zero, the BOC doesn’t want to blow all its rate easing room early and have nothing to help counter the coming recession. For now, they say they will “monitor the evolution of financial vulnerabilities related to the household sector.”

Less than two percent above zero, the BOC doesn’t want to blow all its rate easing room early and have nothing to help counter the coming recession. For now, they say they will “monitor the evolution of financial vulnerabilities related to the household sector.”

At this point in such a garishly extended credit cycle, monitoring is nearly all they can do.