Two of the leading democratic candidate contenders have proposals to greatly curtail share buybacks as a form of illegal market manipulation. Last October the International Monetary Fund’s Global Financial Stability Report, noted “debt-funded payouts” as a form of financial risk-taking by U.S. companies that “can considerably weaken a firm’s credit quality.”

This week a Harvard Business Review article draws the connection between buybacks and extreme dividends funded by debt and low corporate tax rates with weak productivity, shrinking R&D investment, financial fragility, soaring government deficits, and extreme income disparity. See Why Stock Buybacks are Dangerous for the Economy:

Why have U.S. companies done these massive buybacks? With the majority of their compensation coming from stock options and stock awards, senior corporate executives have used open-market repurchases to manipulate their companies’ stock prices to their own benefit and that of others who are in the business of timing the buying and selling of publicly listed shares. Buybacks enrich these opportunistic share sellers — investment bankers and hedge-fund managers as well as senior corporate executives — at the expense of employees, as well as continuing shareholders…

Whether it is corporate debt or government debt that funds additional buybacks, it is the underlying problem of the corporate obsession with stock-price performance that makes U.S. households more vulnerable to the boom-and-bust economy. Debt-financed buybacks reinforce financial fragility. But it is stock buybacks, however funded, that undermine the quest for equitable and stable economic growth. Buybacks done as open-market repurchases should be banned.

In short, buybacks are indefensible and policy change in this area is essential.

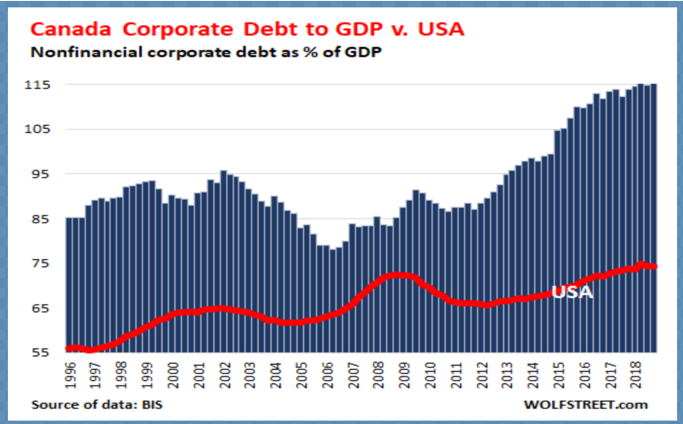

The buyback damage done to corporate balance sheets with record debt to GDP in both Canada and the US is evident in Wolf Richter’s chart below. Canada’s corporate debt to GDP hit a freakish 115% in 2018 versus 70% in the US, and compared with cycle peaks of 95% in Canada in 2002 and 85% in 2008.