As house-bound gamblers have turned their free time to financial markets over the last couple of months, stock and junk debt markets have rebounded sharply and attracted new believers daily. See WSJ: Stuck at home with few entertainment options, more newbies turn to shares; ‘it’s like a gambling game’.

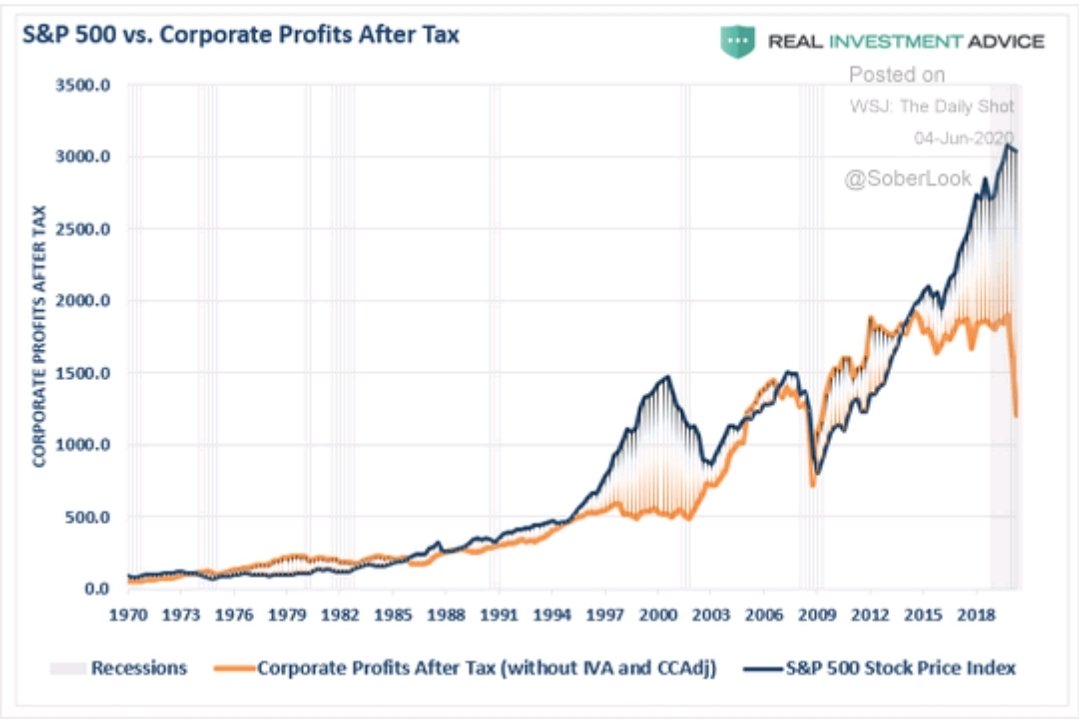

In this environment, things like investing experience, expertise and memory are impediments to blind optimism and have led many to question whether reliable historic ratios will reconnect with asset pricing ever again. Just one example, this chart from Soberlo ok via Real Investment Advice since 1970 shows the awe-inspiring gap in 2020 between the S&P 500 index price (blue) and after-tax corporate profits (in orange). While stock prices have always retraced with corporate profits during past recessions (grey bars), conventional wisdom insists that this time will be different!

ok via Real Investment Advice since 1970 shows the awe-inspiring gap in 2020 between the S&P 500 index price (blue) and after-tax corporate profits (in orange). While stock prices have always retraced with corporate profits during past recessions (grey bars), conventional wisdom insists that this time will be different!

For those interested in higher probability outcomes, John Hussman’s June letter Incubation Phase: Gradually and then Suddenly is worth the reading effort in full. Here’s a few highlights:

Of course, the Great Depression also began with a spectacular financial rebound that bore no relationship to the underlying deterioration on Main Street.

Severe economic recessions often feature what might be called an “incubation phase,” where an exuberant rebound from initial stock market losses becomes detached from the quiet underlying deterioration of economic fundamentals and corporate balance sheets. From the post-crash low of November 13, 1929, the Dow Jones Industrial Average enjoyed a 48% rebound, peaking on April 17, 1930, followed by an 86% collapse by July 8, 1932 (an overall loss of 89% from the September 3, 1929 bull market peak).

…The current “incubation phase” is reminiscent of 2008. Early that year, AIG admitted that it could not “reliably quantify” its losses. In March, Bear Stearns failed. The Associated Press published an article discussing the unprecedented interventions by the Federal Reserve, including Bernanke’s creation of “Maiden Lane” shell companies to absorb bad mortgage-backed debt (which at least represented collateralized debt, unlike the uncollateralized corporate debt the Fed is illegally purchasing today). The article quoted Richard Fuld, the CEO of Lehman Brothers, who argued that this intervention, “from my perspective, takes the liquidity issue for the entire industry off the table.” Clearly, it did not remove the solvency issue.

After the failure of Bear Stearns, after strains in the subprime loan market were fully recognized, and after the Federal Reserve and the U.S. Treasury had already launched unprecedented interventions, the S&P 500 advanced in May 2008 to a level that was within 9% of its October 2007 peak, on the notion that all of the bad news had been “discounted.” The S&P 500 then lost 53% of its value.

…The same sort of slow incubation characterized the financial markets in May 2001. An economic recession had already started two months earlier, and the S&P 500 had been in a bear market for over a year. But as the S&P 500 rebounded within 14% of the March 2000 bubble peak, the Wall Street Journal observed “Though economists are expecting this year to be the economy’s worst since 1991, only a tiny percentage think the economy is in a recession.” The S&P 500 would lose an additional 40% of its value by October 2002, and the technology-heavy Nasdaq 100 would lose an additional 60% of its value, bringing its overall bear market loss to 83%.

Hussman also patiently explains last Friday’s jobs surprise and the illegality of the Fed buying uncollateralized corporate bonds, for anyone interested in facts.

However we choose to respond to present conditions, whatever actions we take or refrain from taking, the mathematical fact is that the probability of the next market crash has risen sharply again over the last two months. Those with something to lose would be wise to take note. Hedgeye CEO Keith McCullough stresses this obvious, yet widely ignored point, in the clip below from The Macro Show. Here’s a direct video link.