After weakening since the end of March, the US dollar index had the most negative month in a decade  in July as US Treasury rates slumped, government spending leapt and plunge protection teams pumped equity futures nightly.

in July as US Treasury rates slumped, government spending leapt and plunge protection teams pumped equity futures nightly.

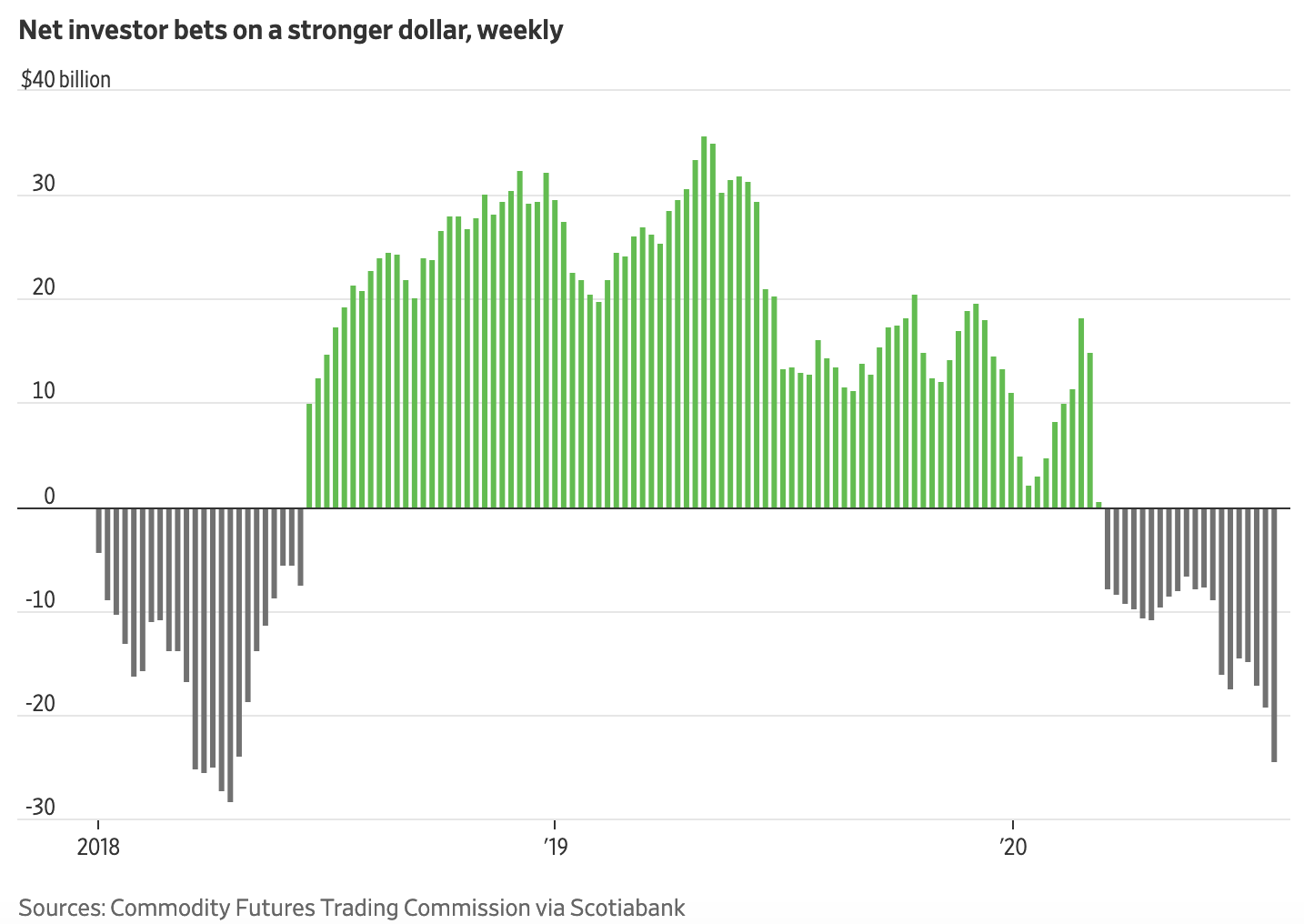

The consensus is now betting on more of the same. As shown on the left, courtesy of the Wall Street Journal, net short positions betting on a weaker greenback today are the largest since the second quarter of 2018 (just before the dollar bounced and risk markets tanked). The latest second-quarter positioning looks similar, see Behind the vast market rally: A tumbling dollar:

Hedge funds and other speculators are favoring everything from the Swedish krona to the Brazilian real, positioning for more dollar weakness. Net investor bets on a weaker dollar recently climbed to their highest level since April 2018, Commodity Futures Trading Commission data compiled by Scotiabank show.

“We are in a stage of very high momentum,” said Ed Al-Hussainy, senior interest-rate and currency analyst at Columbia Threadneedle Investments. He is betting that emerging-market currencies such as the Mexican peso and South African rand will extend their recent rebound. “Everybody is getting caught up in it.”

As the dollar has slumped since March (blue line below), risk assets priced in dollars have staged their typical inverse move, as shown below in my partner Cory Venable’s chart with gold bullion (in orange), copper (in brown) and S&P 500 (in red) leaping (along with most other commodities and cryptocurrencies).

What happens next should be top of the risk management agenda for everyone. The dollar is still the global reserve currency, and the next bounce from oversold conditions threatens carnage for assets on the other end of the teeter-totter.

In 2019, eighty-eight percent of global trade was conducted in the US dollar along with sixty-one percent of all foreign bank reserves and nearly 40% of the world’s loans. To make payments, debtors and buyers of goods and commodities priced in dollars need to acquire the currency through incoming trade flows or selling other assets and currencies. Less global trade means fewer dollars circulating into the hands of those needing them for payments. This is why recessions trigger waves of desperation for dollar liquidity and panicked selling of other assets to get cash.

The corona crisis has accelerated a global trade slump with an unprecedented 92.9% of countries in recession in 2020–well above the 83.8% high recorded during the Great Depression and the 54.3% average of the 15 global recessions since 1871.

The present ‘greatest recession’ is still unfolding, and the next wave of dollar strength stalks risk assets everywhere. Lest we forget.