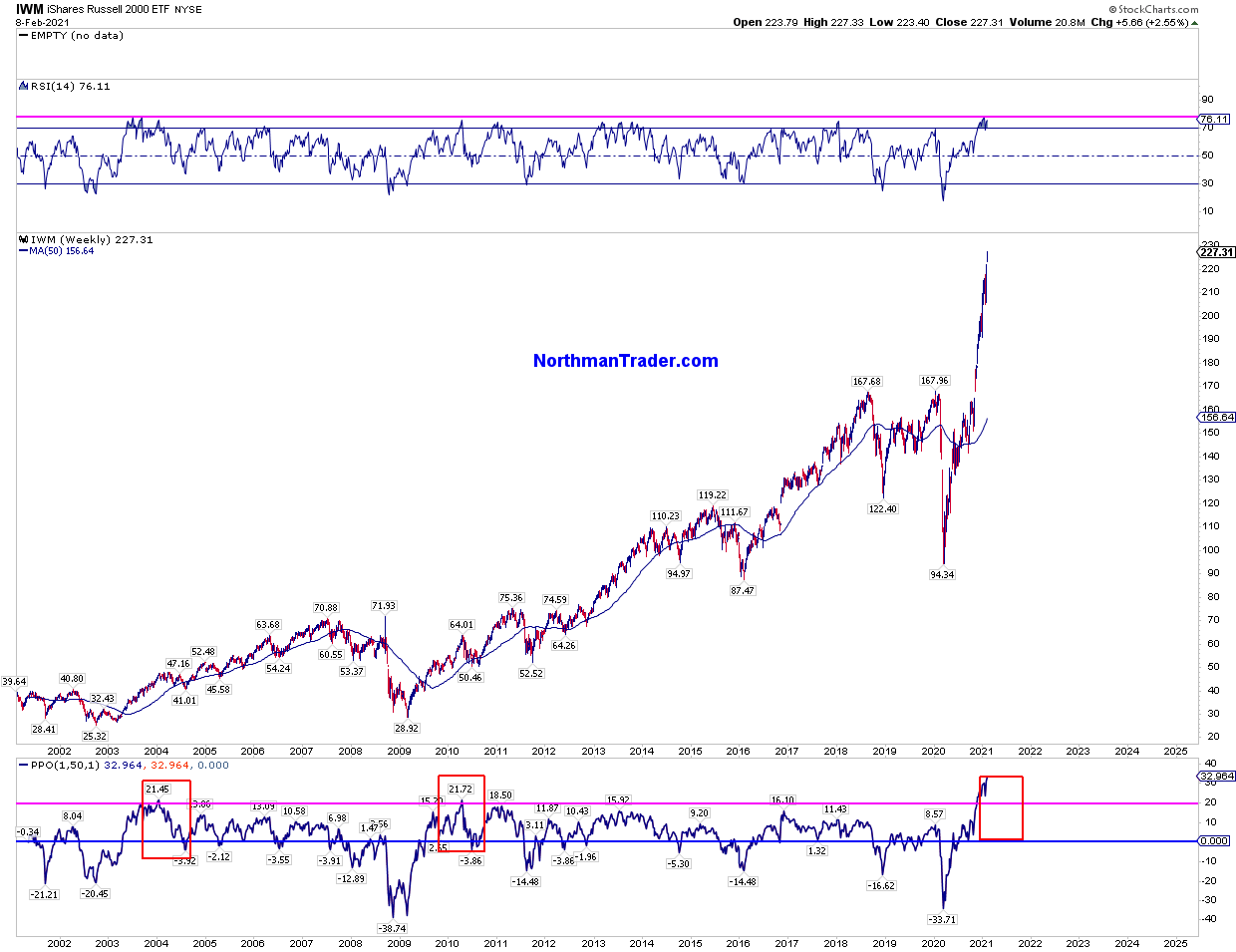

Lest anyone thinks it is just large-cap tech stocks that are trading to Jupiter these days, the chart of small-cap stock prices (the Russell 2000 index below since 2001) shows an incredible 40% gap above their 200-day moving average. Sven Henrich points out in Signal Fire, never before has the weekly chart seen such a steep disconnect, and there is no historical incident where prices have not eventually reconnected with their weekly 50 moving average (blue line below).

A simple reconnect from present levels would mean an average price drop of 31%, and as Sven points out, “…it’s rare for it not to happen for more than a year.”

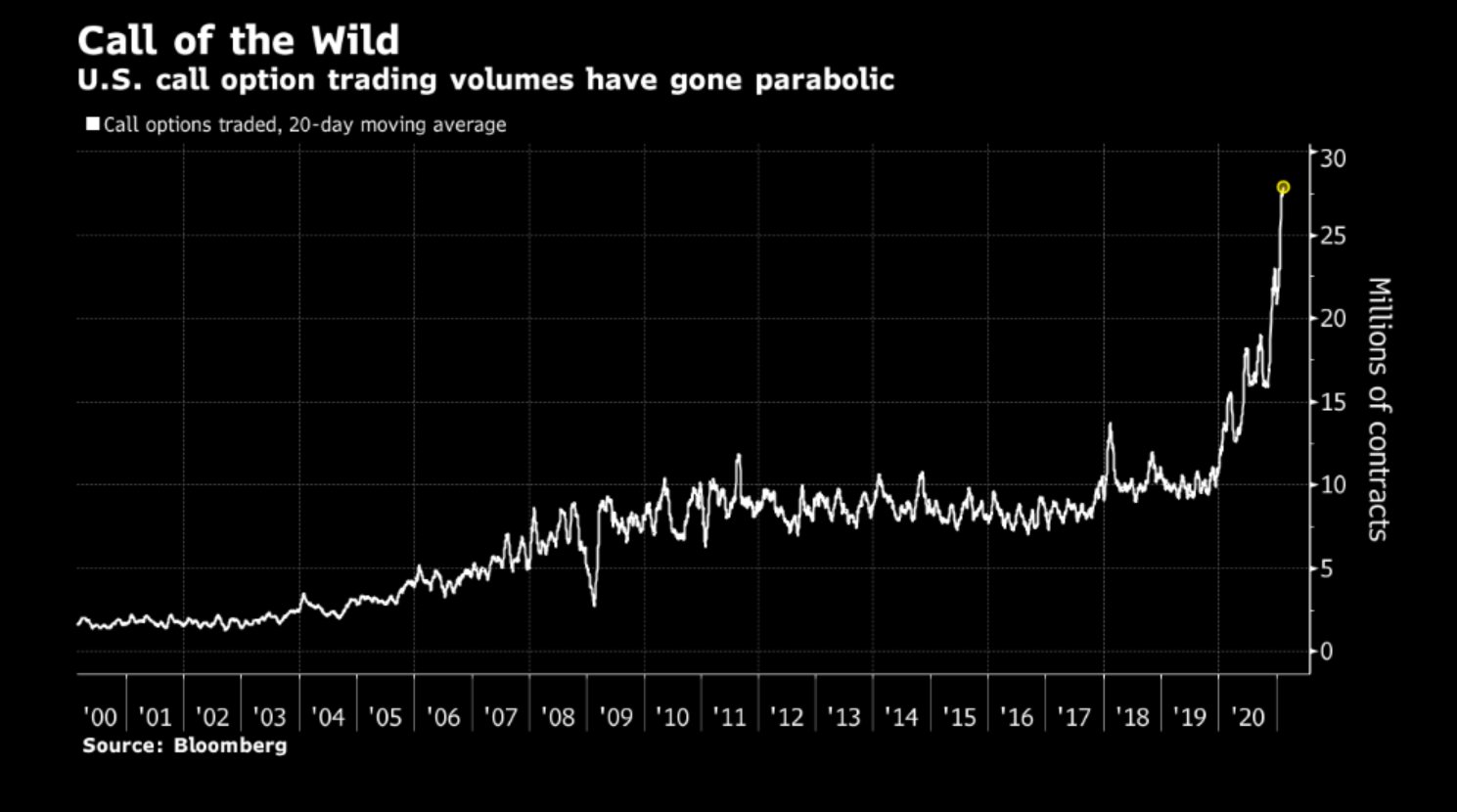

A similar pattern is evident in U.S call trading volumes, which have never been higher, as shown below in this chart since the market top in 2000 courtesy of Bloomberg. Retail is in the house!!

As J.P. Morgan famously remarked: “Nothing so undermines your financial judgment as the sight of your neighbor getting rich.”

In the midst of manic market cycles, it is very human for one to imagine in retrospect where one ‘could have bought’ and ‘should have sold.’ In reality, speculation is much more complicated, attention diverting, peace-destructive, and financially dangerous for individuals than commonly understood. The vast majority of people end up worse off in the end, and this reality is consistent through generations of experience.

While all the classic errors are widely evident in young and inexperienced participants today, other folks, who should know better, are also perpetually at risk of succumbing to the seductive impulses of our lizard brain.

Just one example is the classic behaviour that overtook the greatest mathematician then alive, Sir Isaac Newton, during the South Sea stock bubble of the 1720s. Especially today, it’s important to review such precedents and be reminded of why firm rules and risk-management are essential to real-life outcomes. Read Investors have been making the same mistakes for 300 years. Here’s a taste:

Early in August 1720, Sir Isaac Newton was faced with a choice. In a year when London’s stock market was roaring upward in an utterly unprecedented boom, should he sell the last of his safe investments to buy shares in the South Sea Company? Since January of that year, shares in the firm—one of the largest private companies in history—had gone up eightfold, and had made paper fortunes for thousands.

Already a wealthy man, Newton was usually a cautious investor. As the year began, much of his money was tucked away in various kinds of government bonds—reliable, uneventful investments that delivered a regular stream of income. He did own shares in a few of the larger companies on the exchange, including South Sea, but he had never been a rapid or eager market trader.

That had changed in the past few months, though, as he bought and sold into the rising market seemingly in the hopes of turning a comfortable fortune into an enormous one. By August, he’d unloaded most of his bonds, converting them and other assets into South Sea shares. Now he contemplated selling the rest of his bonds to buy still more shares.

He did sell nearly all of them. It was a disastrous choice. Within three weeks, the market turned. By Christmas, it had utterly collapsed. Newton’s losses reached millions of dollars in 21st-century money.