Oil prices (WTIC) have doubled in just over three months. Average U.S. gas prices, up 10% in just the past week, hit a 30-year high of $4.17 a gallon ($5.44 in California), and North American LNG prices have spiked to all-time highs.

Oil price shocks become deflationary because they trigger demand destruction and economic contraction, especially when the shock coincides with a leap in the cost of food, shelter, and other staples. Where possible, consumers cut back, avoid and substitute; they also cut spending in other areas. A Bloomberg Intelligence report finds that a one-cent change in gas prices influences annual U.S. consumer spending on fuel by about $1.1 billion (See Bond Market sees a recession in the oil shock). This particular fuel spike is happening as reopening trends have more employees commuting back to work.

For all these reasons (and more), this economic cycle faces a greater recessionary impulse than the historical average. It’s also hitting after consumers spent two years buying an unprecedented amount of durable goods which won’t need replacing for s period of years (aka ‘pent down’ demand), and producers and sellers have rebuilt inventories.

Now imagine the urgency to ‘do something about inflationary pressures’ has North American central banks fantasizing about hiking base interest rates some 500% over the next nine months. They can make the slowdown worse, but they can’t help it. Their policy error has already been made: coming into this global crisis with base rates at zero.

Stock owners may hold false hope about monetary magicians, but the bond market does not. Globally, corporate bond prices have been tumbling, driving up borrowing costs for highly levered issuers as credit stress spreads–much more of this to come.

As we expected, North American government bonds are back in favour, attracting capital away from riskier markets. Yesterday, as oil prices leapt, the economically-insightful spread between the two and ten-year U.S. Treasury yield narrowed to .23%, the least since March 2020 when the pandemic was beginning.

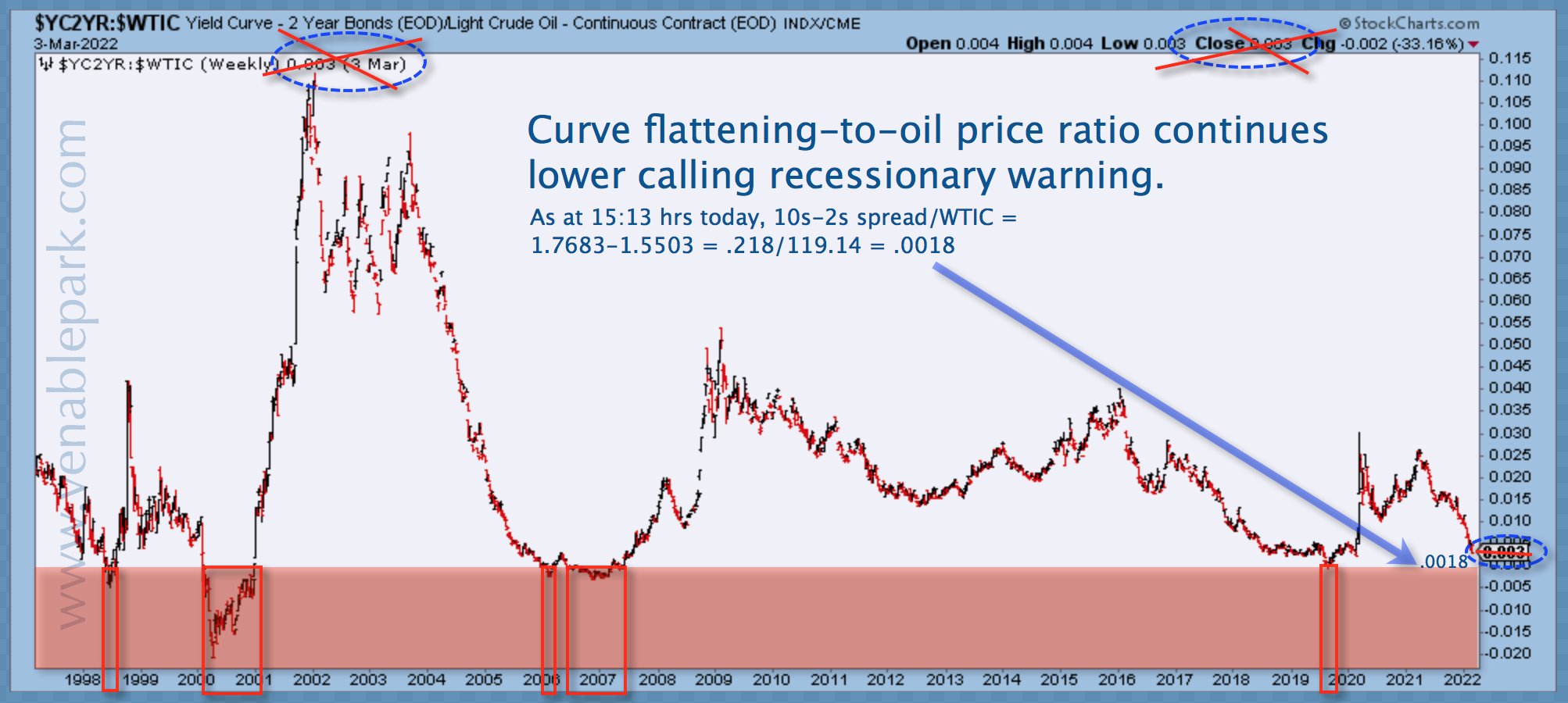

As shown below from my partner Cory Venable, when the yield curve has flattened more than the oil price has spiked, the ratio of the two moves to zero and a recession is underway– it’s.0018 now.

The Canadian Petrodollar has been diving against the greenback over the last year, even as oil prices have soared–another signal for economic pessimism. While the CRB Index (39% allocated to energy contracts, 41% to agriculture, 7% to precious metals, and 13% to industrial metals) typically moves in concert with commodity currencies like the loonie, once the demand cycle has peaked, the loonie leads the CRB down. As Cory highlights below, it did this heading into the 2000 and 2008 recessions.

As of yesterday, the NASDAQ Index followed the lead of small-cap company indices and notched its first 20% decline since March 2020. As in the 2000 and 2008 cycles, the Canadian stock market’s concentration in fossil fuel (12%) and financial companies (32%) has allowed it (-1.5% since November 2021) to hold up better than U.S. markets so far. But make no mistake, Canadian decoupling from U.S bear markets has never lasted historically. With the Canadian housing market and commodity prices extremely overbought, this time is unlikely to be different.

As mean reversion fulfills its destiny, the hit to balance sheets (households, businesses, and lenders) is set to be more severe than any recession since at least the early ’80s. Those who come into this epic repricing cycle with large cash reserves and little debt hold a strong hand–but they will be few.