Our coverage of the VRIC continues with a discussion about the U.S. dollar, and it’s status as a reserve currency, including the role gold plays in protecting wealth and how the dollar’s dominance affects the broader market. Brent Johnson, Danielle Park, Grant Williams, and Russell Gray give their opinions on what is often a hotly contested topic. Here is a direct video link.

Further to comments in the panel discussion about gold outperforming in currencies other than the US dollar, the argument remains rather specious. Things like physical and mental strength, shelter, food, water, a vehicle, a supply of fuel, and medicine all have immediate utility in their own right. Things not used in the present can be stored for future needs or wants. How well something works as a store of value depends on its utility between when it is stored and when it is used.

If a store of value pays an income or reduces expenses for its owner during a holding period, that goes in the benefit column. If it costs to store or hold the item, that’s a negative. In the case of something like gold and other financial assets, the value also depends on whether and in what ratio they can be converted or traded for other items when desired.

Changes in value for the owner will always be a combination of changes in the asset’s market price plus changes in the currency it is priced relative to the currency of one’s spending and needs. It is pretty irrelevant to a Canadian or a European that an asset may have risen in yen unless they have expenses, spending or wants for which they need yen.

As mentioned in my comments on the panel, most assets of international exchange are traded in US dollars. In other words, to get a relative picture of how well a US-denominated asset stored value, one needs to separate the change in its price from the change in its currency exchange relative to one’s home currency. If a US-denominated asset like gold rose in total value by 10% over a particular holding period, while the dollar rose 12% relative to one’s home currency, then we would have fared 2% better holding just US cash rather than gold. And on a risk-adjusted basis, the gold was less liquid (it required a sale and a currency conversion to be useful for our needs) and so came with greater risk and less return.

Over the last decade, the price of gold in U$ appreciated by 3.99% overall and 39.68% relative to the Canadian dollar, but 34.5% of that gain came from the greenback’s appreciation against the loonie. In other words, over ten years, Canadians picked up a gross of 5.18% in notional net benefit by holding gold versus just holding US cash–not an attractive risk-reward equation. However, those who see gold as a form of insurance feel the cost of insurance is justified. And that is ok with me.

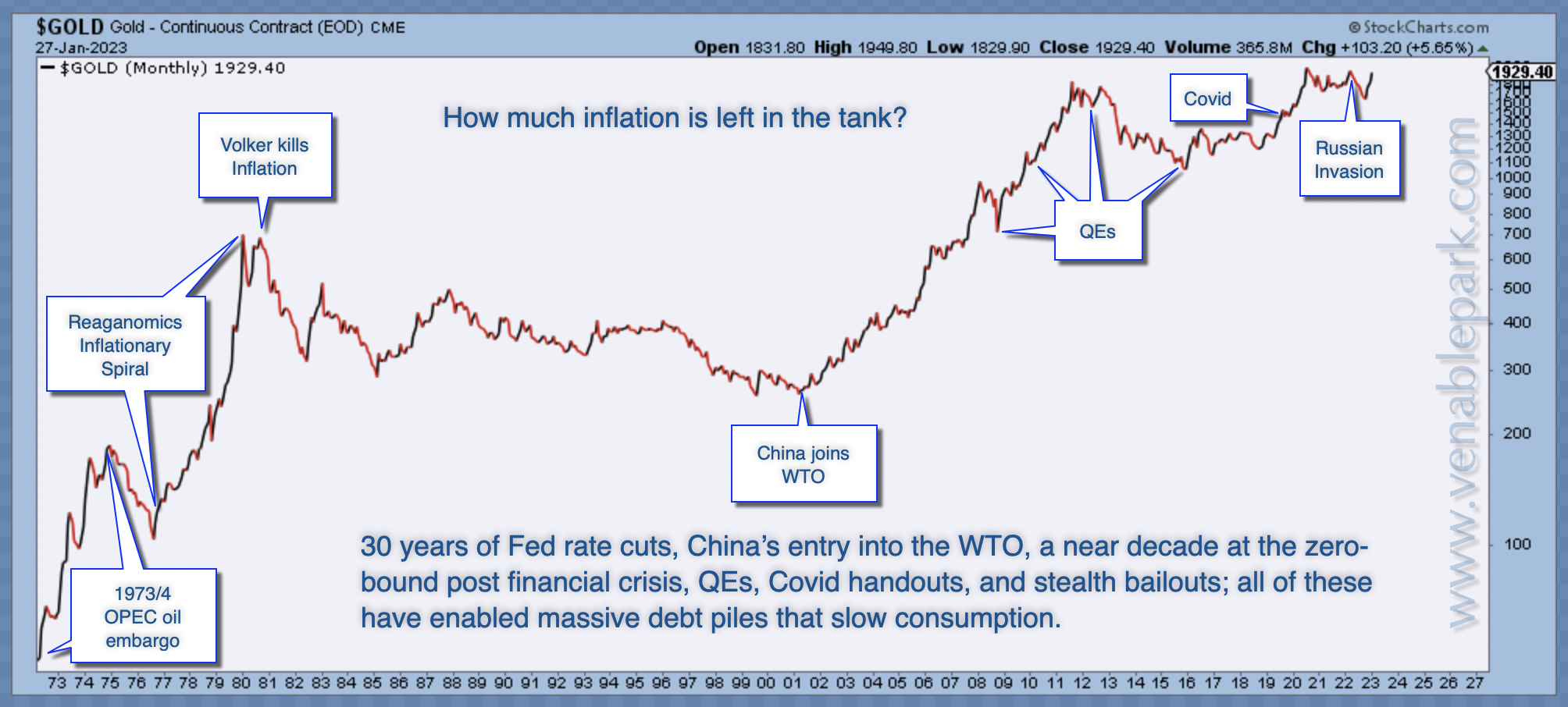

My partner Cory Venable’s chart below shows gold’s price change in US dollars since 1972 and highlights some of the drivers I mentioned in the panel discussion. If inflationary and monetary impulses continue to deflate for the next little while, gold may too.