In April, Canada’s unemployment rate rose to 6.9%, the highest since September 2021 and 210 basis points above the July 2022 cycle low of 4.8% (shown below since 1950).

Beata Caranci, chief economist at TD Bank, expects a recession in the coming quarters and another 100,000 job losses by the fall. See, Canada’s economy is in flux as Trump starts cutting tariff deals.

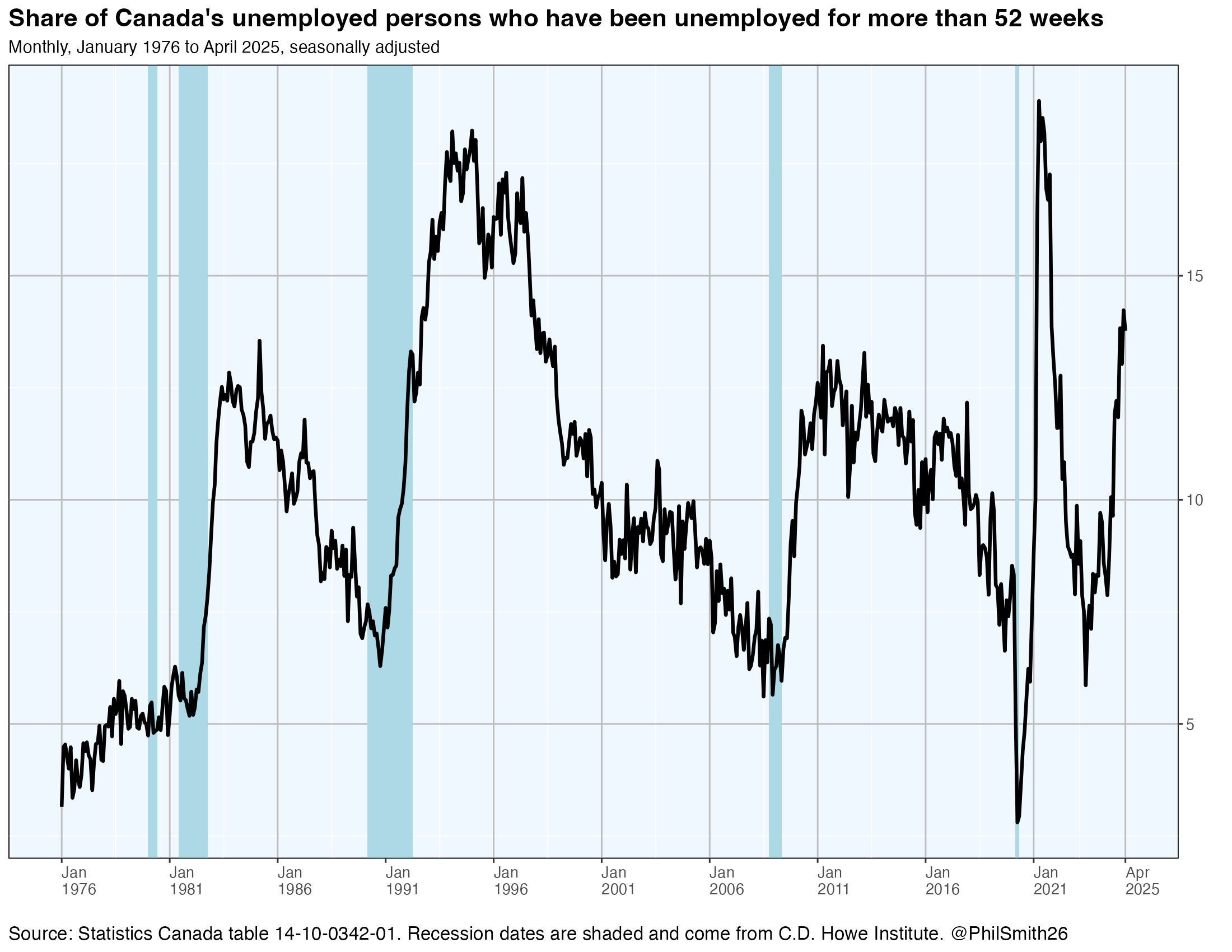

The share of Canadians who have been out of work for over a year is already the third highest since 1976 (monthly, seasonally adjusted, shown below in black). Historically, the unemployment rate has risen for several quarters after recessions (blue bars) have ended.

Despite reports of more people planning to vacation in Canada this summer, the latest from Indeed Canada shows summer job postings down 22% from last year as of early May.

Despite reports of more people planning to vacation in Canada this summer, the latest from Indeed Canada shows summer job postings down 22% from last year as of early May.

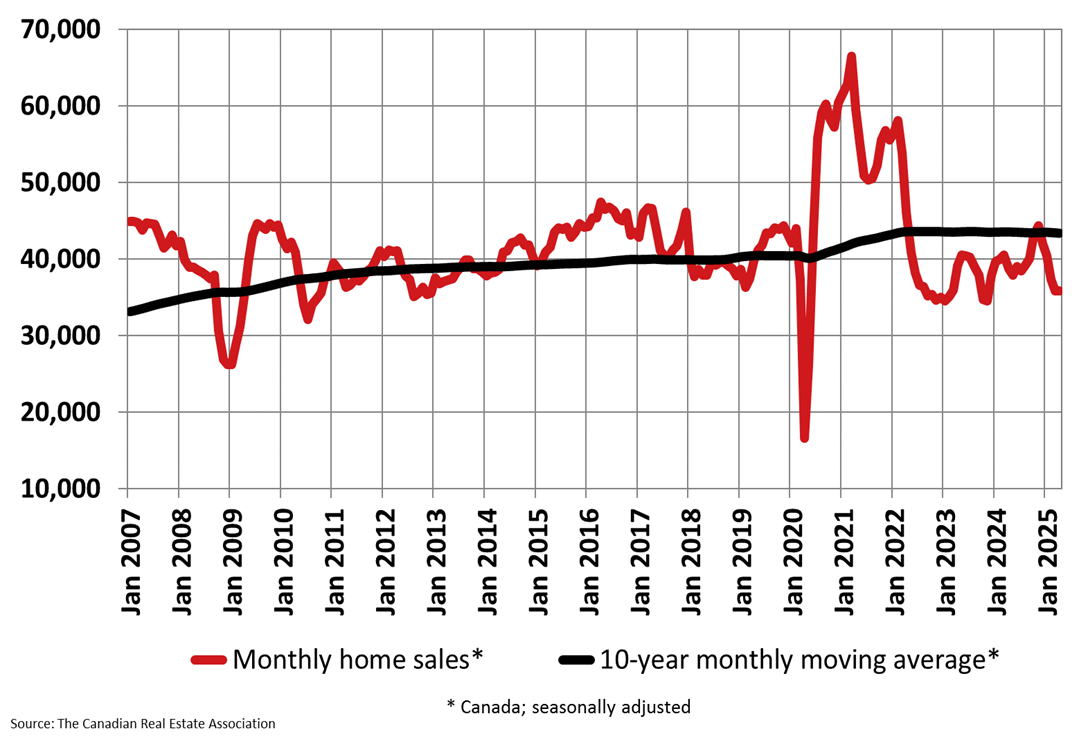

According to the Canadian Real Estate Association, April home sales fell by 0.1% month over month—a fifth consecutive decline—while the consensus expected a 1.0% increase. The year-over-year trend, at -9.8%, has been stuck in negative territory since February, and cumulatively, there’s been a near 42 % drop in sales since the cycle peak in March 2021 (below since 2007).

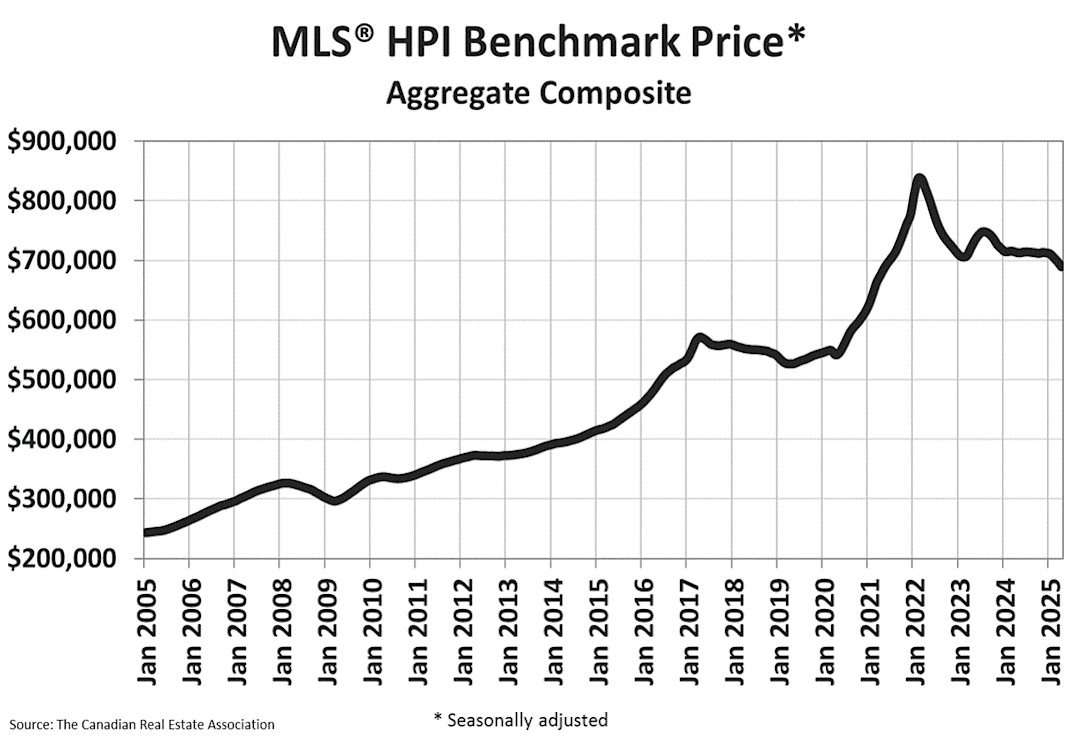

The National Composite MLS® Home Price Index (HPI) declined by 1.2% from March to $679,866 in April 2025 and is -17% from the cycle price peak ($817k) in February 2022 (below since 2005). Nationally, home sale prices in April were still a crushing 9x the median after-tax income of $75,000 (the long-term affordability norm has been 3x).

The National Composite MLS® Home Price Index (HPI) declined by 1.2% from March to $679,866 in April 2025 and is -17% from the cycle price peak ($817k) in February 2022 (below since 2005). Nationally, home sale prices in April were still a crushing 9x the median after-tax income of $75,000 (the long-term affordability norm has been 3x).  A year ago, the Bank of Canada’s (BoC’s) policy rate was 5%, and the average 5-year fixed mortgage rate was around 6.05%. Today, the BoC policy rate has paused at 2.75% since March, and the average 5-year fixed mortgage rate is around 4.39%–still more than double the sub-2% rates many Canadians borrowed at during the pandemic.

A year ago, the Bank of Canada’s (BoC’s) policy rate was 5%, and the average 5-year fixed mortgage rate was around 6.05%. Today, the BoC policy rate has paused at 2.75% since March, and the average 5-year fixed mortgage rate is around 4.39%–still more than double the sub-2% rates many Canadians borrowed at during the pandemic.

According to the BoC’s latest Financial Stability Report, about 60% of all outstanding mortgages in Canada will renew in 2025 or 2026. Based on current market expectations for interest rates, approximately 60% of mortgages in this group will see an increase in their payments at renewal. Most of these are five-year fixed-rate mortgages that were originated or renewed during the pandemic at record-low interest rates.

Canadian insolvency trustees report a steady rise in consumer insolvency filings, including among homeowners. Insolvency Trustee Scott Terrio connected the dots in a LinkedIn post last week:

We all hear a lot about Canadians having used credit for downpayments during the housing boom. But I am also hearing quite alarmingly often how Canadians used credit for the stock market, crypto, etc. Like large numbers borrowed, and by the time they’re meeting with me those investments are all lost. So the banks/lenders are out.

Unfortunately, not just housing is eating away at Canadian financial stability.

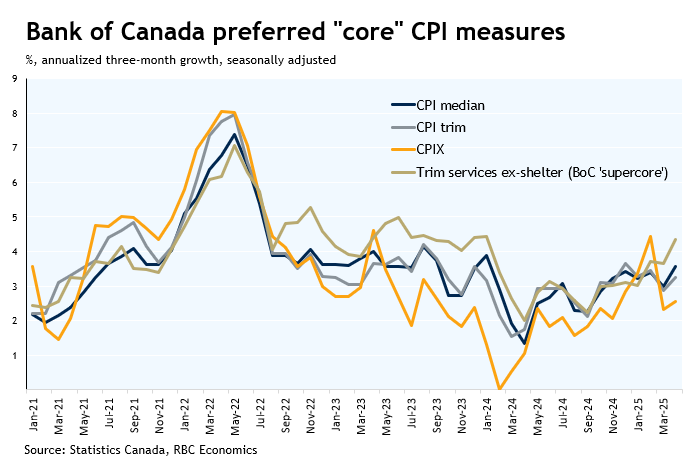

The Bank of Canada’s preferred “core” inflation measures for April—CPI-trim and CPI-median (which exclude the impact of the recent carbon tax reduction)—edged up to 3.1% and 3.2%, respectively, on a larger-than-normal 0.4% month-over-month increase.

This was the first time these metrics had surpassed 3% year over year since the first half of 2024 (shown below since 2021). Higher vehicle and food prices are starting to reflect some impact from tariffs, but the broader upward surprise came from growth in service prices. See, Canadian CPI growth firmed in April, excluding tax changes.

Higher vehicle and food prices are starting to reflect some impact from tariffs, but the broader upward surprise came from growth in service prices. See, Canadian CPI growth firmed in April, excluding tax changes.

Restaurant prices surged 3.6%, travel tours 6.7% year-over-year, and rents rebounded in April. Shelter inflation continued its slow pace of moderation, while mortgage interest costs remain elevated.

The stock market remains in a dream world, wildly disconnected from economic reality. That makes it much more dangerous than average.