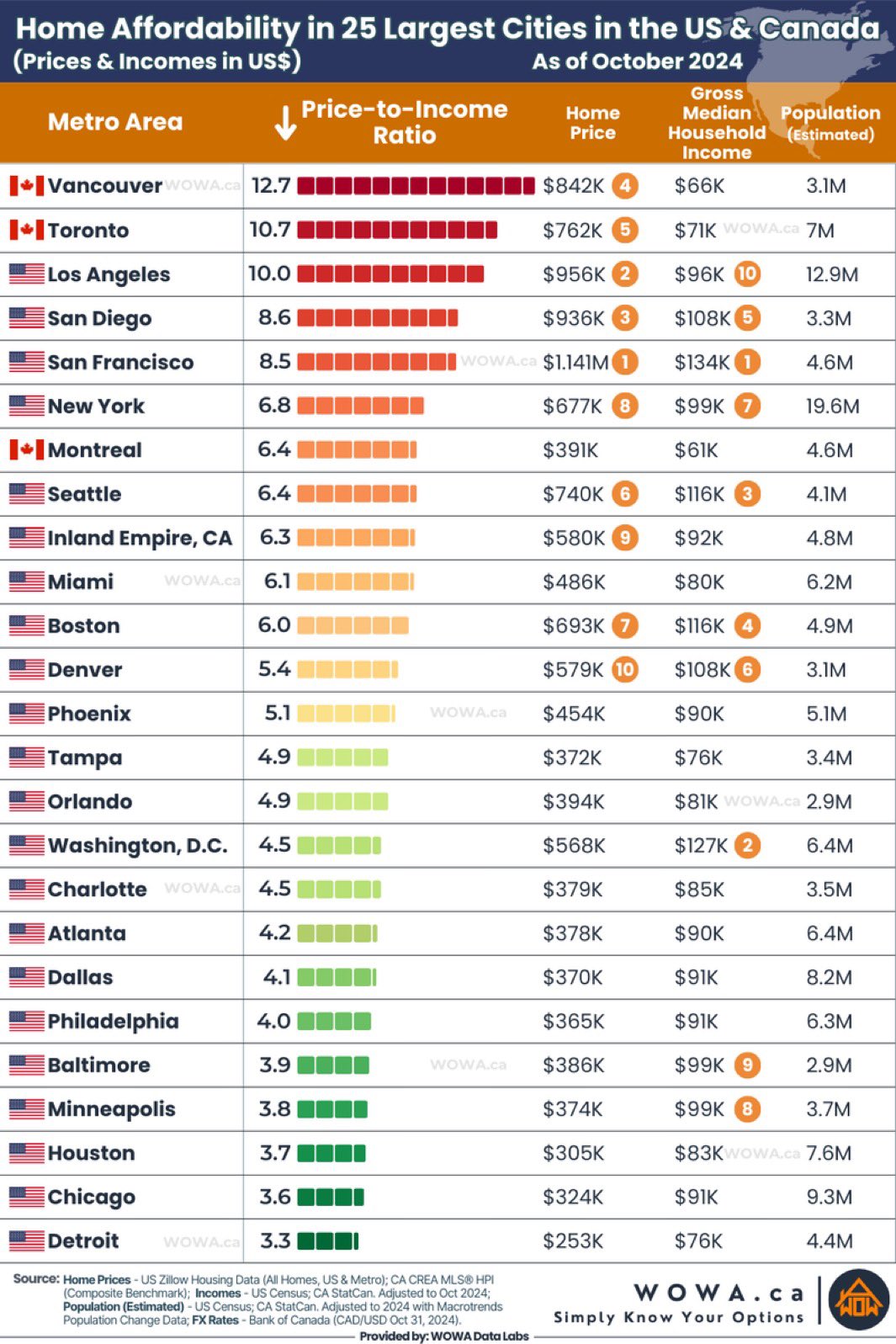

The Canadian government’s plan to constrain population growth by reducing immigration over the next few years is designed to relieve demand pressure on key services like housing, education and health care. That’s needed.

The downsides are that Canada’s economic growth will weaken, and the government will collect less revenue. RBC economists estimate the impact to be about 1 percent less economic growth over the next three years (blue line below) and some $50 billion less government revenue over the five years starting in 2025 (shown in yellow by year). That’s rough, considering that even with the record immigration in 2024, Canada’s economy expanded at just a 1.5% year-over-year annualized growth rate as of the third quarter and an estimated 1% growth rate from the second to the third quarter (quarter over quarter change shown below since 2016, via The Daily Shot).

That’s rough, considering that even with the record immigration in 2024, Canada’s economy expanded at just a 1.5% year-over-year annualized growth rate as of the third quarter and an estimated 1% growth rate from the second to the third quarter (quarter over quarter change shown below since 2016, via The Daily Shot).

The fourth quarter started with flat growth in October. Notwithstanding the weakest loonie since 2020, exports shrank by 1.1%. Capital expenditures from the corporate sector contracted by 27.8%—the largest drop since the second quarter of 2020 and something rarely seen outside of a recession (hat tip, Rosenberg Research). Non-residential construction was flat. Manufacturing has contracted for the past four months with output -4% year-over-year. Government spending was the only engine firing, up 4.8%; Canada’s economy would be contracting without it.

The fourth quarter started with flat growth in October. Notwithstanding the weakest loonie since 2020, exports shrank by 1.1%. Capital expenditures from the corporate sector contracted by 27.8%—the largest drop since the second quarter of 2020 and something rarely seen outside of a recession (hat tip, Rosenberg Research). Non-residential construction was flat. Manufacturing has contracted for the past four months with output -4% year-over-year. Government spending was the only engine firing, up 4.8%; Canada’s economy would be contracting without it.

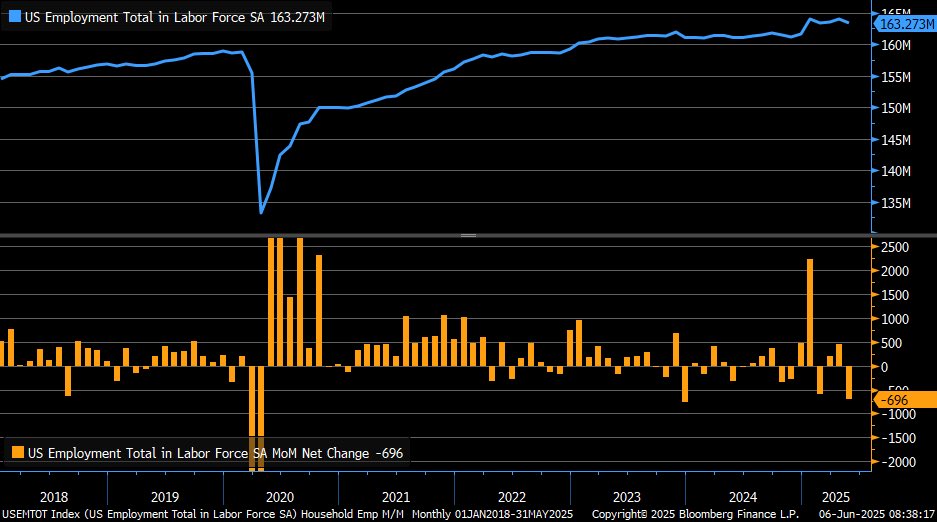

Canada’s unemployment rate has risen 160 basis points from 4.8% in July 2022 to 6.5% in October, faster than any other advanced economy. The standard of living for most Canadians has been weakening for a few years, with real GDP per capita contracting for the sixth consecutive quarter and eight of the last nine quarters—a deterioration not seen since the brutal real estate-led recession of 1980-81.

Next comes the prospect of increased trade tariffs in 2025. Some 21% of Canada’s GDP comes from exports to America (sector breakdown below, courtesy of The Daily Shot), mainly oil and gas and other commodities.

For all the hype about insatiable commodity demand, prices have not rallied with the stock market since the November US election. Despite ongoing wars, oil prices (WTIC) have been flat since May 2021 and are -40% since May 2022. Natural gas is at the same price as five years ago in October 2020 and is -68% since August 2022. Dr. Copper has followed a similar trend—flat since March 2021.

For all the hype about insatiable commodity demand, prices have not rallied with the stock market since the November US election. Despite ongoing wars, oil prices (WTIC) have been flat since May 2021 and are -40% since May 2022. Natural gas is at the same price as five years ago in October 2020 and is -68% since August 2022. Dr. Copper has followed a similar trend—flat since March 2021.

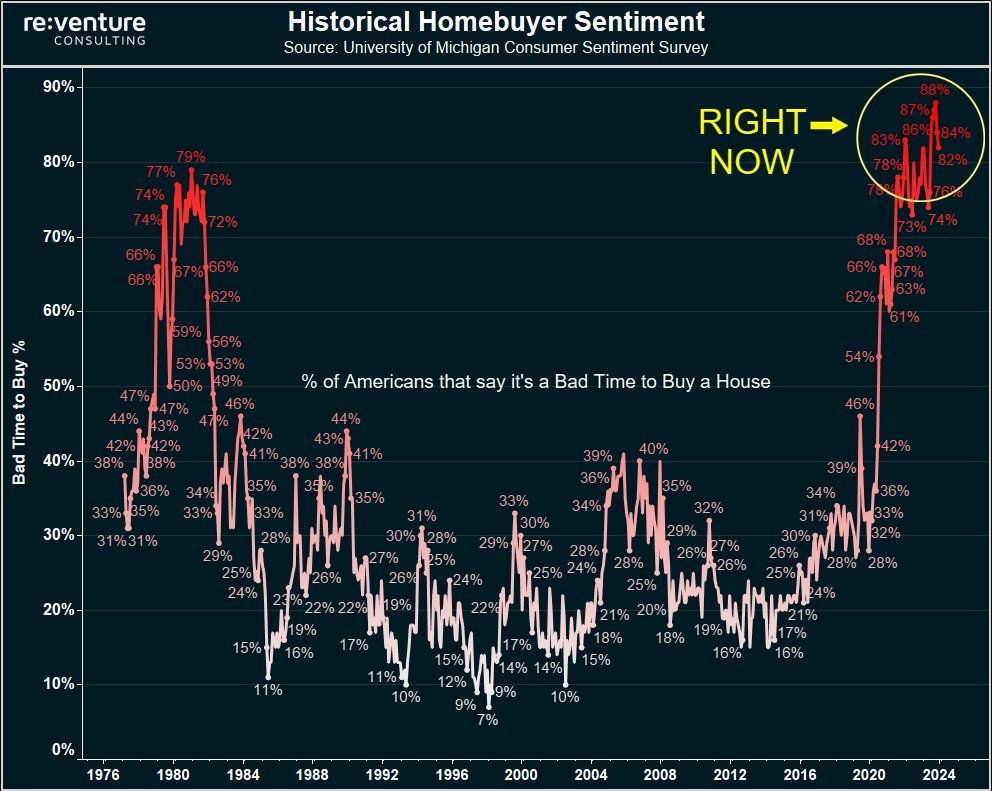

Sustainable growth does not come from more monetary and fiscal gimmicks to further inflate asset price bubbles and unproductive debt. Every country on earth has learned this the hard way through centuries. Japan is the leading example of our generation, but many other countries—like China and Canada—have followed the same playbook and are now suffering the hangover. America had a comeuppance in 2008 but is due for a replay since it doubled down on the same asset bubble-inflating policies.

With real interest rates at their highest in 24 years, capital is no longer free and desperate to take any bet. How well we do in the next decade will depend on how thoughtfully we allocate our resources today. Investments that increase productivity, improve health and training, reduce waste and harm, and lower living expenses are all the right ideas. We can’t afford more of the opposite.